Chapter 3 Attention

Picture yourself driving down a highway. Cars are rushing past, music is playing, your passenger is talking, your phone might be buzzing with notifications, yet somehow you’re able to focus on the road while filtering out most of the chaos around you. This ability to focus on what matters while ignoring distractions is attention in action.

Attention acts like a spotlight, illuminating some information while leaving the rest in darkness. The catch? Your spotlight has limitations. Try to focus on too many things at once, and performance suffers. This is why texting while driving is dangerous, why studying with the TV on is ineffective, and why even hands-free phone conversations impair driving. Understanding attention isn’t just about improving focus; it’s about recognizing the constraints of human consciousness and learning to work within them.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Explain why selective attention is important and how it can be studied.

- Understand early dichotic listening experiments that informed how we think about selective attention, and models that have since been proposed to describe how we selectively attend to some things over others.

- Understand that our cognitive system can control our attentional resources, while recognizing the limits and constraints we face.

3.1 What is Attention?

Figure 3.1: Are you reading these words right here right now? If so, it’s only because you directed your attention toward them. Photo by Justin Chrn on Unsplash

Before we begin exploring attention in its various forms, take a moment to consider how you think about the concept. How would you define attention, or how do you use the term? We certainly use the word very frequently in our everyday language: “ATTENTION! USE ONLY AS DIRECTED!” warns the label on the medicine bottle, meaning be alert to possible danger. “Pay attention!” pleads the weary seventh-grade teacher, not warning about danger (with possible exceptions, depending on the teacher) but urging the students to focus on the task at hand. American psychologist and philosopher William James wrote extensively about attention in the late 1800s. An often quoted passage (James, 1890) beautifully captures how intuitively obvious the concept of attention is, while it remains very difficult to define in concrete and measurable terms:

Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration of consciousness are of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others. (pp. 381–382)

Notice that this description touches on the conscious nature of attention, as well as the notion that what is in consciousness is often controlled voluntarily but can also be determined by external events that capture our attention. These events are often sensory in nature, such as the check engine light turning on in your car or the sound of someone calling your name from across the room. Implied in James’ description is the idea that we seem to have a limited capacity for information processing, and that we can only attend to or be consciously aware of a small amount of information at any given time. If someone captures your attention by calling your name, you are - at least momentarily - pulled away from what you were doing before they called you. This relates to the concept of selective attention; some information can be attended to while other information is blocked out or ignored. The first part of this chapter will address selective attention and some models that have been proposed to explain how we selectively attend to different sensory inputs.

As noted above, we often voluntarily control our attention (a process also known as attentional control). Sometimes we may need to have sustained attention or vigilance to complete a particular task. For example, a crucial issue in World War II was how long an individual could remain highly alert and accurate while watching a radar screen for enemy planes, and this problem led psychologists to study how attention works under such conditions. When watching for a rare event, it is easy to become distracted or allow concentration to lag. However, there are other times when we may need to be flexible and switch our attention to something else. For example, if you are reading while your partner is cooking dinner and the smoke alarm goes off, you should probably switch from paying attention to your book to helping him put out the fire. The second part of this chapter addresses how and how effectively we control our attention, including the consequences of overestimating our ability to attend to multiple sources of information or tasks at the same time, such as texting and driving.

3.2 Selective Attention

The Cocktail Party

Selective attention is the ability to select certain stimuli in the environment to process, while ignoring distracting information. One way to get an intuitive sense of how attention works is to consider situations in which attention is used. A party provides an excellent example for our purposes.

Imagine many people may be milling around, a dazzling variety of colors and sounds and smells, the buzz of many conversations. When walking around, you don’t have to be looking at the person talking; you may start listening with great interest to some gossip while pretending not to hear, and may easily switch to listening to another conversation that grabs your attention as new people walk by. However, once you are engaged in conversation with someone, you quickly become aware that you cannot keep listening to other conversations at the same time. You are also probably not aware of how tight your shoes feel or of the smell of a nearby flower arrangement.

Figure 3.2: Beyond just hearing your name from the clamor at a party, other words or concepts, particularly unusual or significant ones to you, can also snag your attention. Photo by Michael Discenza on Unsplash

On the other hand, if someone behind you mentions your name, you typically notice it immediately and may start attending to that (much more interesting) conversation. This situation highlights an interesting set of observations. We have an amazing ability to select and track one voice or visual object, even when many things are competing for our attention. But at the same time, we seem to be limited in how much we can attend to at one time, which in turn suggests that attention is crucial in selecting what is important. How does it all work?

Dichotic Listening Studies

This cocktail party scenario is the quintessential example of selective attention, and it is essentially what some early researchers tried to replicate under controlled laboratory conditions as a starting point for understanding the role of attention in perception (e.g., Cherry, 1953; Moray, 1959). In particular, they used dichotic listening and shadowing tasks to evaluate the selection process. Dichotic listening simply refers to the situation when two messages are presented simultaneously to an individual, with one message in each ear. In order to control which message the person attends to, the individual is asked to repeat back or “shadow” one of the messages as he hears it. For example, let’s say that a story about a camping trip is presented to John’s left ear, and a story about Abe Lincoln is presented to his right ear. The typical dichotic listening task would have John repeat the story presented to one ear as he hears it. Can he do that without being distracted by the information in the other ear?

People can become pretty good at the shadowing task, and they can easily report the content of the message that they attended to. But what happens to the message they ignored? Typically, people can tell you if the ignored message sounded masculine or feminine, or other physical characteristics of the speech, but they cannot tell you what the message was about. In fact, many studies have shown that people in a shadowing task were not aware of a change in the language of the message (e.g., from English to German; Cherry (1953)), and they didn’t even notice when the same word was repeated in the unattended ear more than 35 times (Moray, 1959)! Only the basic physical characteristics, such as the pitch of the unattended message, could be reported.

On the basis of these types of experiments, we clearly have a limited capacity for processing information for meaning, making the selection process all the more important. How does this selection process work?

Models of Selective Attention

Broadbent’s Filter Model

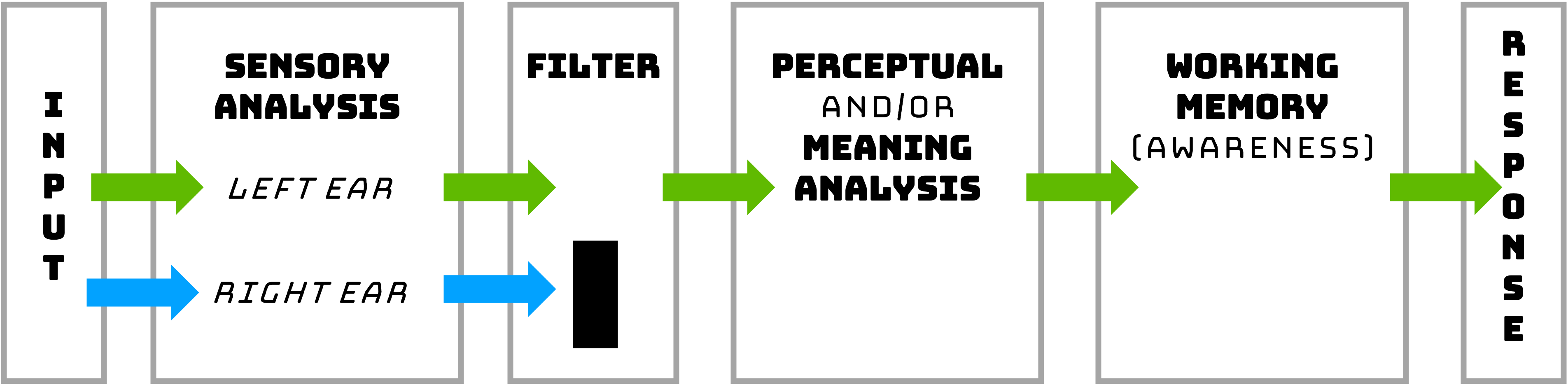

Many researchers have investigated how selection occurs and what happens to ignored information. Donald Broadbent was one of the first to try to characterize the selection process. His Filter Model was based on the dichotic listening tasks described above as well as other types of experiments (Broadbent & Dal Martello, 1958). He found that people select information on the basis of physical features: e.g., the sensory channel (or ear) that a message was coming in, the pitch of the voice, the color or font of a visual message. People seemed vaguely aware of the physical features of the unattended information, but had no knowledge of the meaning. As a result, Broadbent argued that selection occurs very early, with no additional processing for the unselected information. A flowchart of the model might look like Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: Broadbent Filter Model. This figure shows information coming in both the left and right ears. Some basic sensory information, such as pitch, is processed, but an internal filter only allows the information from one ear to be processed further. Only the information from the left ear is transferred to short-term memory (STM) and conscious awareness, and then further processed for meaning. Under this model, ignored information never makes it beyond a basic physical analysis.

Treisman’s Attenuation Model

Broadbent’s model intuitively makes sense, but you may have noticed that one problem is that it cannot account for all aspects of the Cocktail Party Effect. What doesn’t fit? The fact is that you tend to hear your own name when it is spoken by someone, even if you are deeply engaged in a conversation. We mentioned earlier that people in a shadowing experiment were unaware of a word in the unattended ear that was repeated many times — and yet many people noticed their own name in the unattended ear even it occurred only once.

Anne Treisman (1960) carried out a number of dichotic listening experiments in which she presented two different stories to the two ears. In line with the standard procedure, she asked people to shadow the message in one ear. As the stories progressed, however, she switched the stories to the opposite ears. Treisman found that individuals spontaneously followed the story, or the content of the message, when it shifted from the left ear to the right ear. Then they realized they were shadowing the wrong ear and switched back.

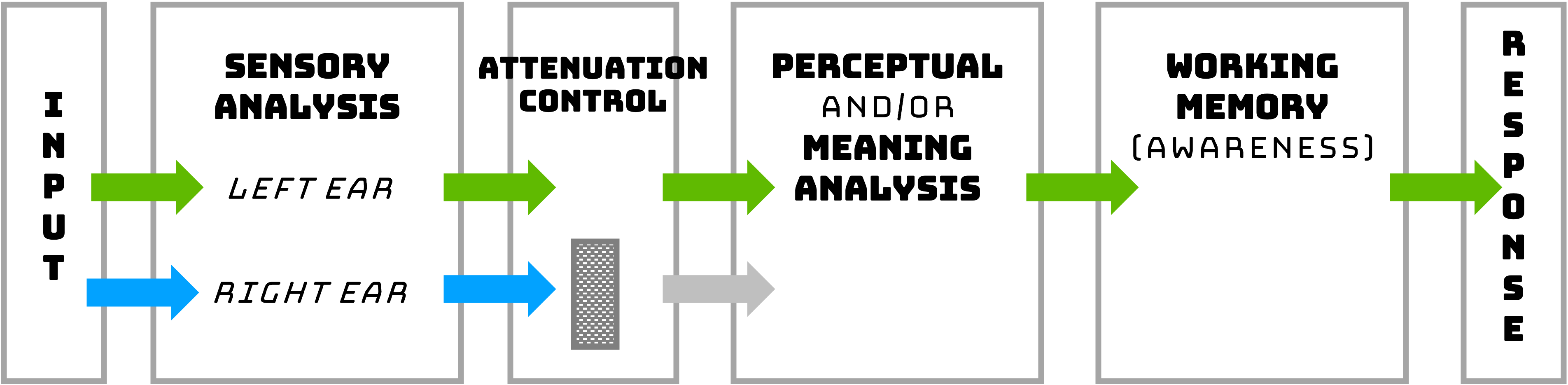

Results like this, and the fact that you tend to hear meaningful information even when you aren’t paying attention to it, suggest that we do monitor the unattended information to some degree on the basis of its meaning. Therefore, Broadbent’s Filter Model can’t be right because it suggests that unattended information is completely blocked at the sensory analysis level. Instead, Treisman suggested that selection starts at the physical or perceptual level, but that the unattended information is not blocked completely, it is just weakened or attenuated. As a result, highly meaningful or pertinent information in the unattended ear will get through the filter for further processing at the level of meaning. A flowchart of her model might look like Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4: Treisman Attenuation Model, an early selection model. This figure shows information coming in both ears, but in contrast to the early selection model, there is no filter that completely blocks nonselected information. Instead, selection of the left ear information strengthens that material, while the nonselected information in the right ear is weakened. However, if the preliminary analysis shows that the nonselected informatio is especially pertinent or meaningful (such as your own name) then the Attenuation Control will instead strengthen the more meaningful information.

Late Selection Models

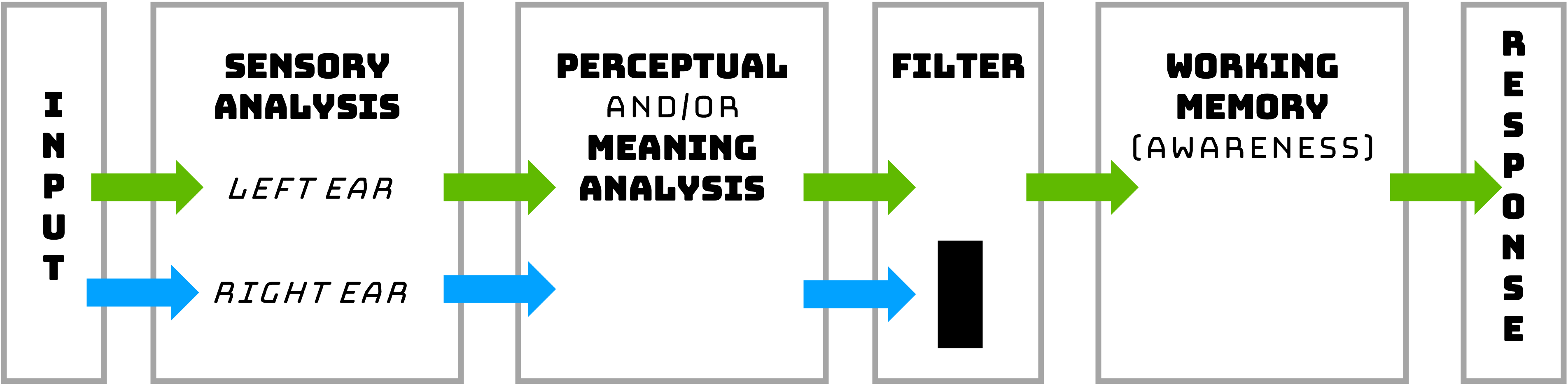

Other selective attention models have been proposed as well. A late selection or response selection model proposed by Deutsch & Deutsch (1963) suggests that all information in the unattended ear is processed on the basis of meaning, not just the selected or highly pertinent information (Figure 3.5). However, only the information that is relevant for the task response gets into conscious awareness. This model is consistent with ideas of subliminal perception; in other words, that you don’t have to be aware of or attending a message for it to be fully processed for meaning.

Figure 3.5: Deutsch and Deutsch late selection model. This figure shows a similar structure to the early selection model, with the major difference being that the location of the selective filter has changed, here being later on in the process. Here, the model makes the assumption that analysis of meaning occurs before selection occurs, but only the selected information becomes conscious.

Load Theory of Attention

Why did researchers keep coming up with different models? Because no model really seemed to account for all the data, some of which indicates that nonselected information is blocked completely, whereas some suggests that it can be processed for meaning. The load theory of attention addresses this apparent inconsistency, suggesting that the stage at which selection occurs can change depending on the task. Johnston & Heinz (1978) demonstrated that under some conditions, we can select what to attend to at a very early stage and we do not process the content of the unattended message very much at all. Analyzing physical information, such as attending to information based on whether it sounds like a masculine or feminine voice, is relatively easy; it occurs automatically, rapidly, and doesn’t take much effort. Under the right conditions, we can select what to attend to on the basis of the meaning of the messages. However, the late selection option—processing the content of all messages before selection—is more difficult and requires more effort. The benefit, though, is that we have the flexibility to change how we deploy our attention depending upon what we are trying to accomplish, which is one of the greatest strengths of our cognitive system.

Selective Attention Beyond the Auditory Domain

This discussion of selective attention has focused on experiments using auditory material, but the same principles hold for other sensory systems as well. Neisser (1979) investigated some of the same questions with visual materials by superimposing two semi-transparent video clips and asking viewers to attend to just one series of actions. As with the auditory materials, viewers often were unaware of what went on in the other video, despite it being clearly visible. Twenty years later, Simons & Chabris (1999) explored and expanded these findings using similar techniques, and triggered a flood of new work in an area referred to as inattentional blindness. In the original study, participants were instructed to complete a task that required paying close attention to certain features of a video clip; in doing so, many of them completely missed other features, such as a man in a gorilla costume walking into the scene (Simons & Chabris, 1999).

Subliminal Perception

The idea of subliminal perception — that stimuli presented below the threshold for awareness can influence thoughts, feelings, or actions — is a fascinating and kind of creepy one. Can messages you are unaware of, embedded in movies or ads or the music playing in the grocery store, really influence what you buy? Many such claims of the power of subliminal perception have been made. One of the most famous came from a market researcher who claimed that the message “Eat Popcorn” briefly flashed throughout a movie increased popcorn sales by more than 50%, although he later admitted that the study was made up (Merikle, 2004). Psychologists have worked hard to investigate whether this is a valid phenomenon. But studying subliminal perception is more difficult than it might seem, because of the difficulty of establishing what the threshold for consciousness is or of even determining what type of threshold is important. For example, Cheesman & Merikle (1984) made an important distinction between objective and subjective thresholds (see also Cheesman & Merikle, 1986). The bottom line is that there is some evidence that individuals can be influenced by stimuli they are not aware of, but how complex the stimuli can be or the extent to which unconscious material can affect behavior is not settled (e.g., Bargh, 2014; Greenwald, 1992; Harris et al., 2013; Merikle, 2004).

3.3 Controlling Attention

As mentioned in the previous section, one of the greatest strengths of our cognitive system is the ability to control how we deploy our cognitive resources to achieve our goals, also known as cognitive control.In the attention domain, we can try to devote all our attention to one thing or we can try to switch our attention to something else. But how good are we at each of these processes? And what happens when we try to do too much at once?

Sustaining Attention

Imagine trying to do your homework with many external and internal distractors: your phone buzzes from an incoming text message, a thought pops into your head about what you want to eat for dinner, a colorful hummingbird flies by your window. If you have a goal to finish your homework assignment before the deadline, you may have to actively focus your attention on your homework despite these distractors. One part of cognitive control is inhibitory control, or the suppression of goal-irrelevant stimuli (attentional inhibition) or responses (response inhibition) (Tiego et al., 2018). Attentional inhibition is thought to be an important aspect of sustaining attention.

Stroop Experiments

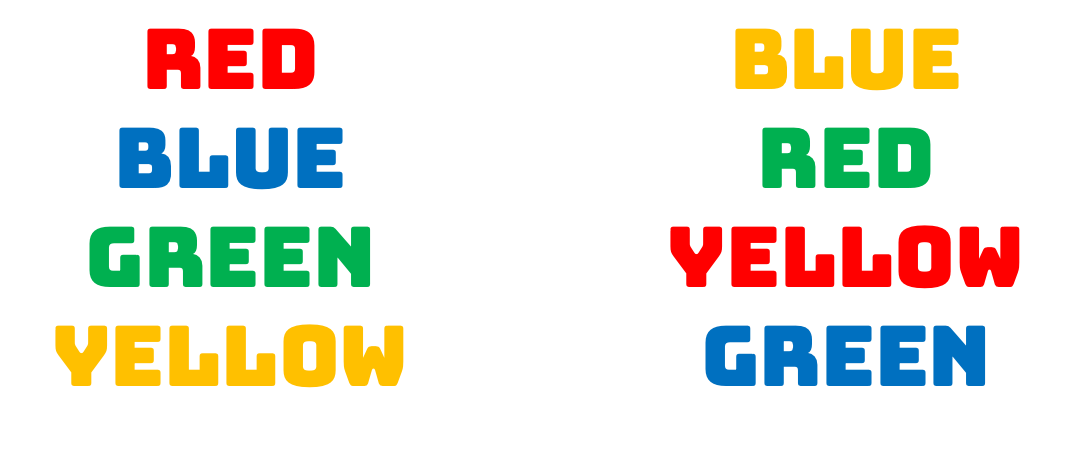

A common task used to study attention is the Stroop task, named for J.R. Stroop who described it in one of the most highly cited experimental psychology papers ever published (Stroop, 1935). In the classic Stroop task, participants are shown words in different colors, and instructed to say out loud the color of the word (not the word itself) as quickly and accurately as they can. That is, their task is to pay attention to the ink color, and ignore anything else that might distract them. Sometimes words match the color they are printed in, such as the words on the left in Figure 3.6. Other times words are printed in a color that differs from their meanings, such as the words on the right.

Figure 3.6: Example of congruent (left) and incongruent (right) stimuli in a classic Stroop paradigm.

When the word meaning matches its ink color, or they are congruent, the task is pretty easy and participants respond relatively quickly and accurately. However, when the word meaning doesn’t match its ink color, or they are incongruent, participants tend to respond slower and make more errors (often by reading out the word, rather than its color). Try it yourself! Even with the simple example above, you might notice that you get tripped up with the incongruent stimuli. This is because with incongruent stimuli there is interference between processing the physical features of the word (color) and its semantics (meaning), and we need to inhibit the irrelevant yet salient semantic information to succeed at the task. Even if we try to attend to just one thing, we can still be thrown off if other things are distracting enough.

Switching Attention

In our previous example about doing homework, we called attention-grabbing items or events “distractors.” However, sometimes our goals change or important new information comes up, and we want or need to switch our attention to something else. In this case, such inputs aren’t distractions, but rather helpful cues to switch our attention. Up until now, it may have sounded like having your attention pulled away or actively switching attention is quite easy and natural. However, it turns out that switching attention is cognitively demanding and can impair performance.

Task Switching Experiments

A large body of work studies cognitive flexibility, or how we adapt our cognition to new or changing environments or goals. A typical task switching experiment involves first training participants to complete two or more simple tasks that relate to the same set of stimuli, and then having them switch back and forth between them (Monsell, 2003). For example, researchers can train participants to classify the number (e.g., odd or even) or the letter (e.g., vowel or consonant) when shown a number-letter pair. If a subject had to complete the number classification task for these stimuli – E1, 8Z, D3, 7U – the correct responses would be “odd”, “even”, “odd”, “odd”. But if they were cued to switch back and forth between the two tasks for the same stimuli in this example, the correct responses would be “odd”, “consonant”, “odd”, “vowel”.

In order to successfully switch in a task-switching experiment, it is thought that some mental processes must happen, which can include switching attention between stimuli or concepts, retrieving different goal states and task-set rules, and activating or adjusting responses (Monsell, 2003). Many different task-switching paradigms have been used in psychology and cognitive neuroscience to understand how we switch between doing different tasks. One reliable behavioral finding is that participants are slower and less accurate in their responding on switch trials compared to non-switch trials. This suggests that switching is cognitively demanding and comes at a cost.

Multitasking

In spite of the evidence of our limited capacity, many of us like to think that we can do several things at once. Some people claim to be able to multitask without any problem: reading a textbook while watching television or talking with friends, talking on the phone while playing video games, even texting while driving. The fact is that sometimes we seem to juggle several things at once, particularly when some or all of the tasks are “easy.” For example, as we talk to someone while walking down the street, we don’t need to think consciously about what muscle to contract to take our next step. In fact, paying attention to automated skills can lead to a breakdown in performance, or “choking” (e.g., Beilock & Carr, 2001). But what about higher level, more mentally demanding tasks? Is it possible to perform multiple complex tasks at the same time?

In one study, two participants were trained to take dictation for spoken words while reading unrelated material for comprehension (Spelke et al., 1976). To establish a baseline performance and determine the amount of cognitive resources needed for each task, the participants first performed each task separately. Then they performed both tasks simultaneously. Next, they completed extensive practice of one hour per day, five days a week, for 17 weeks. Remarkably, the participants were able to learn dictation for lists of words and read for comprehension without any decline in performance for either task. The authors suggested that this may indicate there are no fixed limits on our attentional capacity. However, when the participants were asked to switch to different tasks, such as reading aloud instead of silently, performance was initially impaired. Therefore, the ability to multitask appears to be specific to well-learned tasks.

Unless a task is fully automated, many researchers suggest that “multitasking” doesn’t exist – even when you think you are multitasking, you are really just rapidly switching your attention back and forth. A body of research using dual-task paradigms suggests that earlier estimates of our capacity for doing two or more things at the same time were overly optimistic; some cognitive operations cause “bottlenecks” that require exclusive use of a cognitive resource and therefore cannot be done concurrently (Pashler, 1993). This has been supported in experimental psychology and applied to real-world situations, including distracted driving (see next section) and emergency medicine. One review paper argued that it is impossible to multitask unless behaviors are completely automatic, and that in emergency medicine, physicians are instead rapidly switching between small tasks, which can come at a cost (Skaugset et al., 2016).

Distracted Driving

In today’s technology-driven society, questions regarding multitasking while using electronic devices have become increasingly relevant. Specifically, research investigating the effects of multitasking while driving—under controlled conditions—has produced some surprising results. While distractions such as applying makeup, tending to children in the back seat, fiddling a CD player, or eating a bowl of cereal while driving can impair performance, we often overestimate our ability to multitask behind the wheel. Despite this, cars are being built with ever more advanced technological capabilities that further encourage multitasking. Given these factors, it is important to ask how effective we truly are at dividing our attention in such situations.

Figure 3.7: If you look at your phone for just 5 seconds while driving at 55mph, that means you have driven the length of a football field without looking at the road. Photo by Alexandre Boucher on Unsplash

Most people acknowledge the distraction caused by texting while driving and the reason seems obvious: Your eyes are off the road and your hands and at least one hand (often both) are engaged while texting. However, the problem is not simply one of occupied hands or eyes, but rather that the cognitive demands on our limited capacity systems can seriously impair driving performance (Strayer et al., 2011). The effect of a cell phone conversation on performance (such as not noticing someone’s brake lights or responding more slowly to them) is just as significant when the individual is having a conversation with a hands-free device as with a handheld phone; the same impairments do not occur when listening to the radio or a book on tape (Strayer & Johnston, 2001). Moreover, studies using eye-tracking devices have shown that drivers are less likely to later recognize objects that they did look at when using a cell phone while driving (Strayer & Drews, 2007). These findings demonstrate that cognitive distractions such as cell phone conversations can produce inattentional blindness, or a lack of awareness of what is right before your eyes (see also Simons & Chabris, 1999). Sadly, although we may think that we can multitask while driving, in fact the percentage of people who can truly perform cognitive tasks without impairing their driving performance is estimated to be only about 2% (Watson & Strayer, 2010).

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

By the end of their first decade of life, typically developing children have mastered the complex cognitive operations required to comply with the rules, such as stopping themselves from acting impulsively, paying attention to parents and teachers in the face of distraction, and sitting still despite boredom. For children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), exercising self-control is a unique challenge. Some people used to believe that children with ADHD were willfully noncompliant due to moral or motivational deficits (Still, 1902). However, scientists now know that noncompliance observed in ADHD can be explained by many factors, including neurological dysfunction.

ADHD is the most commonly diagnosed childhood behavior disorder, affecting 3% to 7% of children in the United States, according to the American Psychiatric Association (2000). The core symptoms of ADHD are organized into two clusters: hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention. Hyperactive and impulsive symptoms are closely related, the former involving moving perpetually (even when stillness is expected) and the latter including acting without considering repercussions. Inattentive symptoms describe difficulty with organization and task follow-through, as well as a tendency to be distracted by external stimuli. Broadly speaking, boys are more likely than girls to experience symptoms from the hyperactive and impulsive cluster (Hartung & Widiger, 1998), while girls are more likely to experience symptoms from the inattentive cluster (Quinn & Madhoo, 2014). Gender differences in how ADHD presents, combined with other factors such as how parents, teachers, or clinicians notice and interpret ADHD symptoms, have contributed to many women and girls with ADHD not being diagnosed or treated (Quinn & Madhoo, 2014).

Key Takeaways

- It may be useful to think of attention as a mental resource, one that is needed to focus on and fully process important information, especially when there is a lot of distracting “noise” threatening to obscure the message.

- Our selective attention system allows us to find or track an object or conversation in the midst of distractions. Whether the selection process occurs early or late in the analysis of those events has been the focus of considerable research, and in fact how selection occurs may very well depend on the specific conditions.

- With respect to controlling our attention, in general we can only perform one cognitively demanding task at a time, and even then, we can be distracted from performing that task if the conditions are right. Switching back and forth between different tasks also comes at a cost.

- When we focus our attention on one task or source of information, we may not even be aware of unattended events even though they might seem too obvious to miss. This type of inattention blindness can occur even in well-learned tasks, such as driving while talking on a cell phone.

Exercises

- Discuss: Discuss the implications of the different models of selective attention for everyday life. For instance, what advantages and disadvantages would be associated with being able to filter out all unwanted information at a very early stage in processing? What are the implications of processing all ignored information fully, even if you aren’t consciously aware of that information?

- Practice: Think of examples of when you feel you can successfully multitask and when you can’t. What aspects of the tasks or the situation seem to influence divided attention performance? How accurate do you think you are in judging your own multitasking ability?

- Apply: What are the public policy implications of current evidence of inattentional blindness as a result of distracted driving? Should this evidence influence traffic safety laws? What additional studies of distracted driving would you propose?

3.4 Glossary

cognitive control

The ability to regulate how we deploy our cognitive resources to achieve our goals

inattentional blindness

The failure to notice a fully visible object when attention is devoted to something else.

limited capacity

The notion that humans have limited mental resources that can be used at a given time.