Chapter 2 Perception

Right now, as you read these words, your brain is performing an extraordinary feat. Light waves bouncing off this page are hitting your eyes, but somehow you’re not seeing meaningless patterns of black marks; you’re seeing letters, words, and ideas. Your perceptual system takes fragmented, upside-down, constantly shifting sensory information and transforms it into a coherent, meaningful experience of the world. Perception isn’t just passive reception of information; it’s an active process of interpretation and construction.

Studying perception reveals something profound about human experience: the world you perceive isn’t simply “out there” – it’s actively constructed by your brain.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Review and summarize the capacities and limitations of human sensation.

- Identify the key structures of the eye and the role they play in vision.

- Describe how sensation and perception work together through sensory interaction, selective attention, sensory adaptation, and perceptual constancy.

- Give examples of how our expectations may influence our perception, resulting in illusions and potentially inaccurate judgments.

2.1 Sensation and Perception

The ability to detect and interpret the events that are occurring around us allows us to respond to these stimuli appropriately (Gibson et al., 2000). In most cases the system is successful, but it is not perfect. In this chapter we will discuss the strengths and limitations of these capacities, focusing on both sensation — the stimulation of sensory receptor cells, which is converted to neural impulses — and perception — our experience as a result of that stimulation. Sensation and perception work seamlessly together to allow us to experience the world through our eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and skin, but also to combine what we are currently learning from the environment with what we already know about it (prior knowledge) in order to make judgments and to choose appropriate behaviors.

Humans possess powerful sensory capacities that allow us to sense the kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, smells, and tastes that surround us. Our eyes detect light energy and our ears pick up sound waves. Our skin senses touch, pressure, hot, and cold. Our tongues react to the molecules of the foods we eat, and our noses detect scents in the air. The human sensory and perceptual systems are wired for accuracy, and people are exceedingly good at making use of the wide variety of information available to them (Stoffregen & Bardy, 2001).

In many ways, our senses are quite remarkable. The human eye can detect the equivalent of a single candle flame burning 30 miles away and can distinguish among more than 300,000 different colors. The human ear can detect sounds as low as 20 hertz (vibrations per second) and as high as 20,000 hertz, and it can hear the tick of a clock about 20 feet away in a quiet room. We can taste a teaspoon of sugar dissolved in two gallons of water, and we are able to smell one drop of perfume diffused in a three-room apartment. We can feel the wing of a bee on our cheek dropped from one centimeter above (Galanter, 1962).

Seeing

Whereas other animals rely primarily on hearing, smell, or touch to understand the world around them, humans rely in large part on vision. Thus, vision will be the primary sense we focus on in this chapter. A large part of our cerebral cortex is devoted to seeing, and we have substantial visual skills. Seeing begins when light falls on the eyes, initiating the process of transduction, the conversion of light detected by receptor cells to electrical impulses that are transported to the brain. Once this visual information reaches the visual cortex, it is processed by a variety of neurons that detect colors, shapes, and motion, and that create meaningful perceptions out of the incoming stimuli. The brain does this in part by combining incoming information with our expectations and prior knowledge about the world.

The Sensing Eye and the Perceiving Visual Cortex

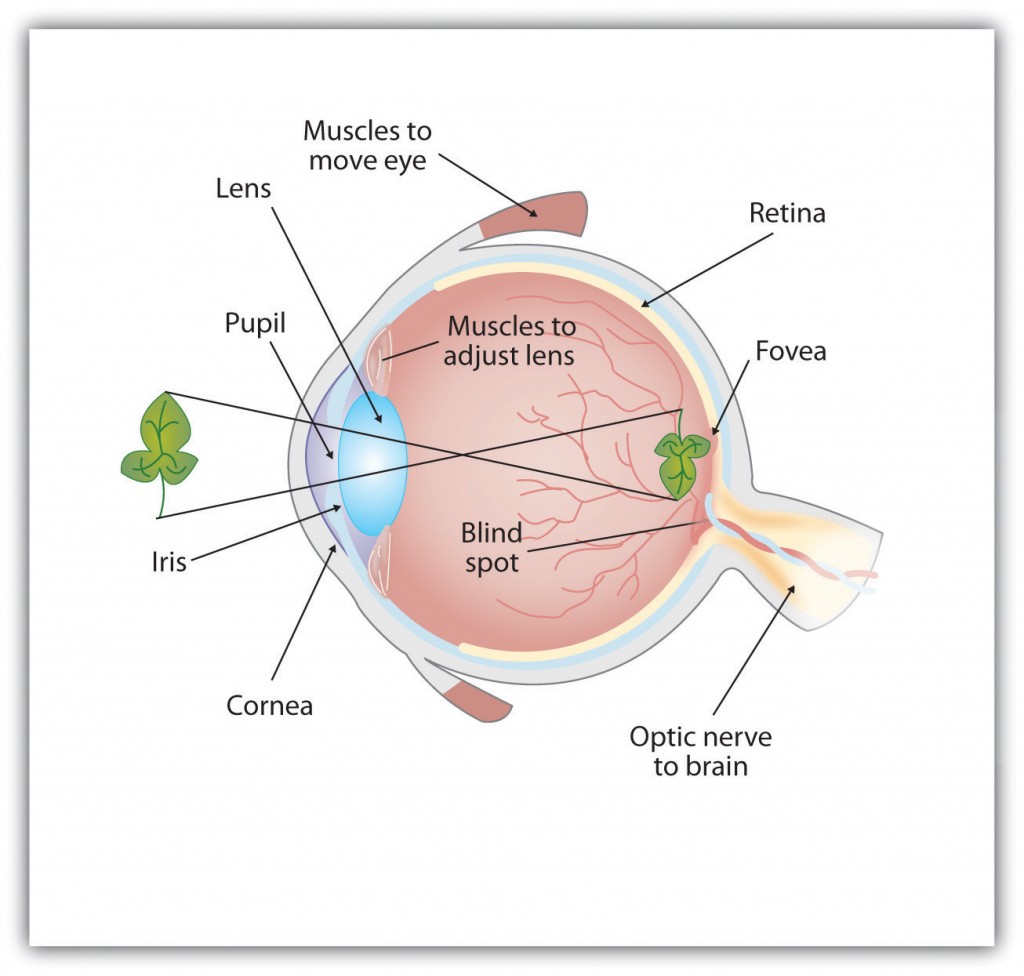

As you can see in Figure 2.1, light enters the eye through the cornea, a clear covering that protects the eye and begins to focus the incoming light. The light then passes through the pupil, a small opening in the center of the eye. The pupil is surrounded by the iris, the colored part of the eye that controls the size of the pupil by constricting or dilating in response to light intensity. When we enter a dark movie theater on a sunny day, for instance, muscles in the iris open the pupil and allow more light to enter. Complete adaptation to the dark may take up to 20 minutes.

Figure 2.1: Anatomy of the Human Eye. Behind the pupil is the lens, a structure that focuses the incoming light on the retina, the layer of tissue at the back of the eye that contains photoreceptor cells. Rays from the top of the image strike the bottom of the retina and vice versa, and rays from the left side of the image strike the right part of the retina and vice versa, causing the image on the retina to be upside down.

Behind the pupil is the lens, a structure that focuses the incoming light on the retina, the layer of tissue at the back of the eye that contains photoreceptor cells. Rays from the top of the image strike the bottom of the retina and vice versa, and rays from the left side of the image strike the right part of the retina and vice versa, causing the image on the retina to be upside down.

The retina contains layers of neurons specialized to respond to light. As light falls on the retina, it first activates receptor cells known as rods and cones. The activation of these cells then spreads to the bipolar cells and then to the ganglion cells, which gather together and converge, like the strands of a rope, forming the optic nerve. The optic nerve is a collection of millions of ganglion neurons that sends vast amounts of visual information, via a structure in the middle of the brain called the thalamus, to the visual cortex, which starts at the back of the brain (thus validating to the phrase, “I have eyes in the back of my head”). Because the retina and the optic nerve are active processors and analyzers of visual information, it is appropriate to think of these structures as an extension of the brain itself.

Rods are sensory receptor neurons that specialize in detecting black, white, and gray colors. There are about 120 million rods in each eye. The rods do not provide a lot of detail about the images we see, but because they are highly sensitive to shorter-waved (darker) and weak light, they help us see in dim light — for instance, at night. Because the rods are located primarily around the edges of the retina, they are particularly active in peripheral vision (when you need to see something at night, try looking slightly to the side of what you want to see in order to activate more of your highly sensitive rod receptors). Cones are sensory receptor neurons that are specialized in detecting fine detail and colors. The five million or so cones in each eye enable us to see in color, but they operate best in bright light. The cones are located primarily in and around the fovea, which is the central point of the retina.

To demonstrate the difference between rods and cones in attention to detail, choose a word in this text and focus on it. Do you notice that the words a few inches to the side seem more blurred? This is because the word you are focusing on strikes the detail-oriented cones, while the words surrounding it strike the less-detail-oriented rods, which are located on the periphery.

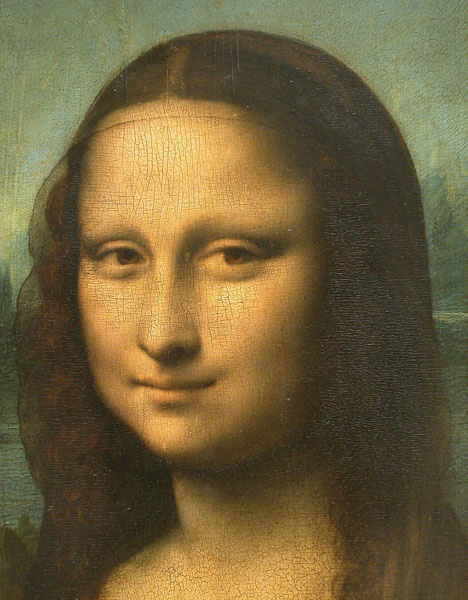

Margaret Livingstone (2000) (Figure 2.2) found an interesting effect that demonstrates the different processing capacities of the eye’s rods and cones — namely, that the Mona Lisa’s smile, which is widely referred to as “elusive,” is perceived differently depending on how one looks at the painting. Because Leonardo da Vinci painted the smile in low-detail brush strokes, the smile is actually better perceived by the rods in our peripheral vision than by the cones. Livingstone found that people rated the Mona Lisa as more cheerful when they were instructed to focus on her eyes than they did when they were asked to look directly at her mouth. As Livingstone put it, “She smiles until you look at her mouth, and then it fades, like a dim star that disappears when you look directly at it.”

Figure 2.2: Mona Lisa’s smile.

The brain’s visual cortex is made up of specialized neurons that turn the sensations they receive from the optic nerve into meaningful representations of the world. Because there are no photoreceptor cells at the place where the optic nerve leaves the retina, a hole or blind spot in our vision is created (see Figure 2.3). When both of our eyes are open, we don’t experience a “hole” in our awareness because our eyes are constantly moving, and one eye makes up for what the other eye misses. The visual system is also designed to deal with this problem if only one eye is open — the visual cortex simply fills in the small hole in our vision with similar patterns from the surrounding areas, and we never notice the difference. The visual system’s ability to cope with the blind spot is another example of how sensation and perception work together to create meaningful experience.

Figure 2.3: Blind Spot Demonstration. You can get an idea of the extent of your blind spot (the place where the optic nerve leaves the retina) by trying this: close your left eye and stare with your right eye at the cross in the diagram. You should be able to see the elephant image to the right (don’t look at it, just notice that it is there). If you can’t see the elephant, move closer or farther away until you can. Now slowly move so that you are closer to the image while you keep looking at the cross. At one distance (around a foot or so depending on your zoom), the elephant will completely disappear from view because its image has fallen on the blind spot.

Perceiving Depth

Depth perception is the ability to perceive three-dimensional space and to accurately judge distance. Without depth perception, we would be unable to drive a car, thread a needle, or simply navigate our way around the supermarket (Howard, 2002).

Depth perception is the result of our use of depth cues, messages from our bodies and the external environment that supply us with information about space and distance. Binocular depth cues are depth cues that are created by retinal image disparity — that is, the space between our eyes — and which thus require the coordination of both eyes. One outcome of retinal disparity is that the images projected on each eye are slightly different from each other. The visual cortex automatically merges the two images into one, enabling us to perceive depth. Three-dimensional movies make use of retinal disparity by using 3-D glasses that the viewer wears to create a different image on each eye. The perceptual system quickly, easily, and unconsciously turns the disparity into 3-D.

An important binocular depth cue is convergence, the inward turning of our eyes that is required to focus on objects that are less than about 50 feet away from us. The visual cortex uses the size of the convergence angle between the eyes to judge the object’s distance. You will be able to feel your eyes converging if you slowly bring a finger closer to your nose while continuing to focus on it. When you close one eye, you no longer feel the tension — convergence is a binocular depth cue that requires both eyes to work.

Although the best cues to depth occur when both eyes work together, we are able to see depth even with one eye closed. Monocular depth cues are depth cues that help us perceive depth using only one eye (Sekuler & Blake, 2006). Some of the most important cues are summarized in Table 2.1.

| Name | Description | Example | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position | We tend to see objects higher up in our field of vision as farther away. | The fence posts at right appear farther away not only because they become smaller but also because they appear higher up in the picture. |  |

| Relative size | Assuming that the objects in a scene are the same size, smaller objects are perceived as father away. | at right, the cars in the distance appear smaller than those nearer to us. |  |

| Linear perspective | Parallel lines appear to converge at a distance. | We know that the tracks at right are parallel. When they appear closer together, we determine they are farther away. |  |

| Light and shadow | The eye receives more reflected light from objects that are closer to us. Normally, light comes from above, so darker images are in shadow. | We see the images at right as extending and indented according to their shadowing. If we invert the picture, the images will reverse. |  |

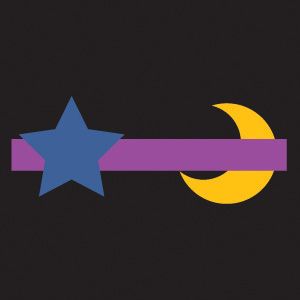

| Interposition | When one object overlaps another object, we view it as closer. | At right, because the blue star covers the pink bar, it is seen as closer than the yellow moon. |  |

| Aerial perspective | Objects that appear hazy, or that are covered with smog or dust, appear farther away. | The artist who pained the picture on the right used aerial perspective to make the clouds more hazy and this appear farther away. |  |

Perceiving Form

One of the important functions of the visual system is the perception of form. German psychologists in the 1930s and 1940s, including Max Wertheimer (1880-1943), Kurt Koffka (1886-1941), and Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967), argued that we create forms out of their component sensations based on the idea of the gestalt, a meaningfully organized whole. The idea of the gestalt is that the “whole is more than the sum of its parts.” Some examples of how gestalt principles lead us to see more than what is actually there are summarized in Table 2.2.

| Principle | Description | Example | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

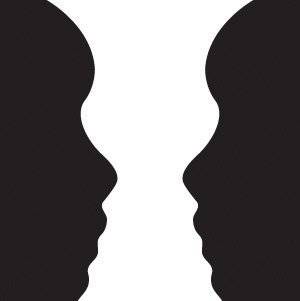

| Figure and ground | We structure input so that we always see a figure (image) against a ground (background). | At right, you may see a vase or you may see two faces, but in either case, you will organize the image as a figure against a ground. |  |

| Similarity | Stimuli that are similar to each other tend to be grouped together. | You are more likely to see three similar columns among the XYX characters at right than you are to see four rows. |  |

| Proximity | We tend to group nearby figures together. | Do you see four or eight images at right? Principles of proximity suggest that you might see only four. |  |

| Continuity | We tend to perceive stimuli in smooth, continuous ways rather than in more discontinuous ways. | At right, most people see a line of dots that moves from the lower left to the upper right, rather than a line that moves from the left and then suddenly turns down. The principle of continuity leads us to see most lines as following the smoothest possible path. |  |

| Closure | We tend to fill in gaps in an incomplete image to create a complete, whole object. | Closure leads us to see a single spherical object at right rather than a set of unrelated cones. |  |

2.2 Perception: Information Integration

The eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and skin sense the world around us, and in some cases perform preliminary information processing on the incoming data. But by and large, what we end up “seeing” or experiencing is a result of our brain’s interpretation of the sensory information coming in, rather than a direct read out of that information. When we look out the window at a view of the countryside, or when we look at the face of a good friend, we don’t just see a jumble of colors and shapes — we see, instead, an image of a countryside or an image of a friend (Goodale & Milner, 2006). How our brain interprets and integrates sensory information in a way that leads to our everyday experience largely depends on attention, working memory, and other cognitive processes that will be discussed in future chapters of this book.

How the Perceptual System Interprets the Environment

This process of understanding involves the automatic operation of a variety of essential perceptual processes. One of these is sensory interaction — the working together of different senses to create experience. For example, sensory interaction is involved when taste, smell, and texture combine to create the flavor we experience in food. It is also involved when we enjoy a movie because of the way the images and the music work together.

](images/ch2/mcgurk.png)

Figure 2.4: Watch The McGurk Effect on YouTube

Although you might think that we understand speech only through our sense of hearing, it turns out that the visual aspect of speech is also important. One example of sensory interaction is shown in the McGurk effect — an error in perception that occurs when we misperceive sounds because the audio and visual parts of the speech are mismatched. You can witness the effect yourself by viewing the video in Figure 2.4.

Other examples of sensory interaction include the experience of nausea that can occur when the sensory information being received from the eyes and the body does not match information from the vestibular system (Flanagan et al., 2004) and synesthesia — an experience in which one sensation (e.g., seeing a number) creates experiences in another (e.g., hearing a sound). Most people do not experience synesthesia, but those who do link their perceptions in unusual ways, for instance, by experiencing color when they taste a particular food or by hearing sounds when they see certain objects (Ramachandran et al., 2005).

A more recent example of sensory interaction illustrates how sounds can directly shape our visual perception (Williams et al., 2022). Researchers showed people noisy images (e.g., a blurry image of a plane/bird) paired with naturalisitic sounds. Perception – whether they saw it as a plane or bird – was shaped by the sound that the image was paired with. If the image was paired with the sounds of a bird, people were more likely to see the image as a bird instead of a plane. This research shows that our perceptual experience of one sense (e.g., vision) is shaped by other senses (e.g., hearing).

A second fundamental process of perception is sensory adaptation — a decreased sensitivity to a stimulus after prolonged and constant exposure. When you step into a swimming pool, the water initially feels cold, but after a while you stop noticing it. After prolonged exposure to the same stimulus, our sensitivity toward it diminishes and we no longer perceive it. The ability to adapt to the things that don’t change around us is essential to our survival, as it leaves our sensory receptors free to detect the important and informative changes in our environment and to respond accordingly. We ignore the sounds that our car makes every day, which leaves us free to pay attention to the sounds that are different from normal, and thus likely to need our attention. Our sensory receptors are alert to novelty and are fatigued after constant exposure to the same stimulus.

If sensory adaptation occurs with all senses, why doesn’t an image fade away after we stare at it for a period of time? The answer is that, although we are not aware of it, our eyes are constantly flitting from one angle to the next, making thousands of tiny movements (called saccades) every minute. This constant eye movement guarantees that the image we are viewing always falls on fresh receptor cells. What would happen if we could stop the movement of our eyes? Psychologists have devised a way of testing the sensory adaptation of the eye by attaching an instrument that ensures a constant image is maintained on the eye’s inner surface. Participants are fitted with a contact lens that has a miniature slide projector attached to it. Because the projector follows the exact movements of the eye, the same image is always projected, stimulating the same spot, on the retina. Within a few seconds, interesting things begin to happen. The image will begin to vanish, then reappear, only to disappear again, either in pieces or as a whole. Even the eye experiences sensory adaptation (Yarbus, 1967).

One of the major problems in perception is to ensure that we always perceive the same object in the same way, even when the sensations it creates on our receptors change dramatically. The ability to perceive a stimulus as constant despite changes in sensation is known as perceptual constancy. Consider our image of a door as it swings. When it is closed, we see it as rectangular, but when it is open, we see only its edge and it appears as a line. But we never perceive the door as changing shape as it swings — perceptual mechanisms take care of the problem for us by allowing us to see a constant shape.

The visual system also corrects for color constancy. Imagine that you are wearing blue jeans and a bright white T-shirt. When you are outdoors, both colors will be at their brightest, but you will still perceive the white T-shirt as bright and the blue jeans as darker. When you go indoors, the light shining on the clothes will be significantly dimmer, but you will still perceive the T-shirt as bright. This is because we put colors in context and see that, compared with its surroundings, the white T-shirt reflects the most light (McCann, 1992). In the same way, a green leaf on a cloudy day may reflect the same wavelength of light as a brown tree branch does on a sunny day. Nevertheless, we still perceive the leaf as green and the branch as brown.

Why are computers still so bad at perception?

Computer vision refers to machines or algorithms that are built to mimic the human sensation and perception system. As we’ve learned, perception does not work like a camera, where we experience exactly what comes in through our senses. Instead, what we perceive is influenced by many factors, such as other sensory input, prior experiences, and expectations. Programming all of these components into a computer is difficult, and one reason why computer vision isn’t as good as we might expect it to be.

Another complication is that there are still significant gaps in our understanding of the human perceptual system. For instance, consider this: if perception is an integrative process that takes time, whatever we see now is no longer what is in front of us. Yet, humans can do amazing time-sensitive feats like hitting a 90-mph fastball in a baseball game. It appears then that a fundamental function of visual perception is not just to know what is happening around you now, but actually to make an accurate inference about what you are about to see next (Enns & Lleras, 2008), so that you can keep up with the world. Understanding how this future-oriented, predictive function of perception is achieved in the brain is a largely unsolved challenge, and just another piece of the puzzle that computer vision models will have to solve as well.

Illusions

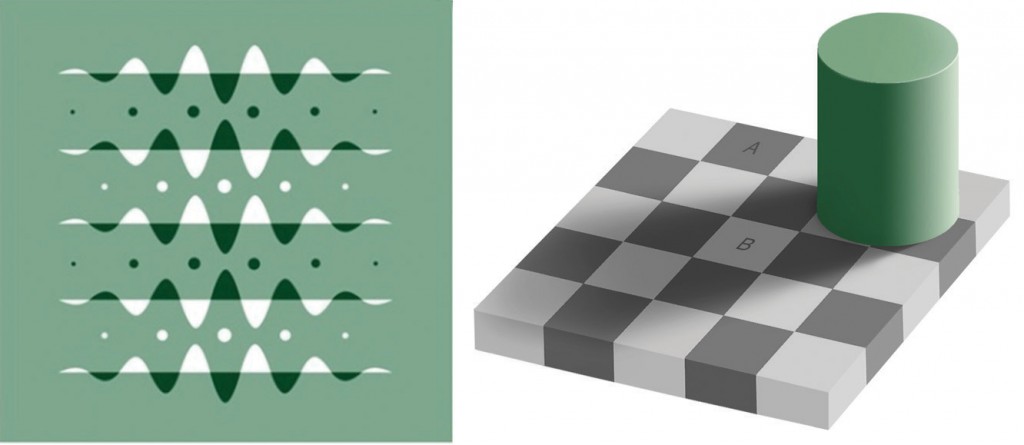

Figure 2.5: Optical Illusions as a Result of Brightness Constancy (Left) and Color Constancy (Right). Look carefully at the snakelike pattern on the left. Are the green strips really brighter than the background? Cover the white curves and you’ll see they are not. Square A in the right-hand image looks very different from square B, even though they are exactly the same.

Although our perception is very accurate, it is not perfect. Illusions occur when the perceptual processes that normally help us correctly perceive the world around us are fooled by a particular situation so that we see something that does not exist or that is incorrect. Figure 2.5 presents two situations in which our normally accurate perceptions of visual constancy have been fooled.

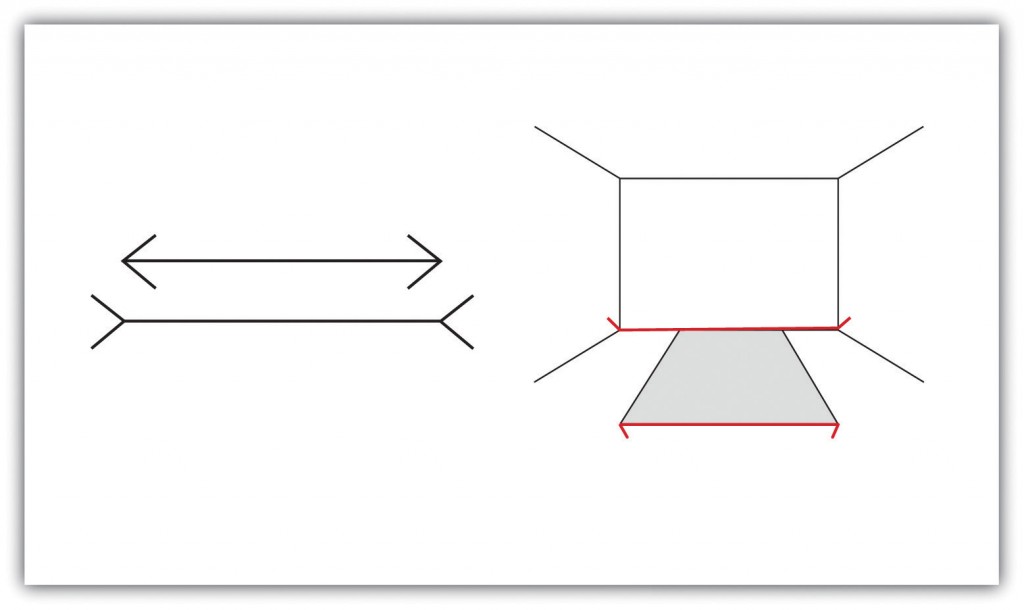

Another well-known illusion is the Mueller-Lyer illusion (see Figure 2.6). The line segment in the bottom arrow looks longer to us than the one on the top, even though they are both actually the same length. It is likely that the illusion is, in part, the result of the failure of monocular depth cues — the bottom line looks like an edge that is normally farther away from us, whereas the top one looks like an edge that is normally closer.

Figure 2.6: The Mueller-Lyer illusion makes the line segment at the top of the left picture appear shorter than the one at the bottom. The illusion is caused, in part, by the monocular distance cue of depth — the bottom line looks like an edge that is normally farther away from us, whereas the top one looks like an edge that is normally closer.

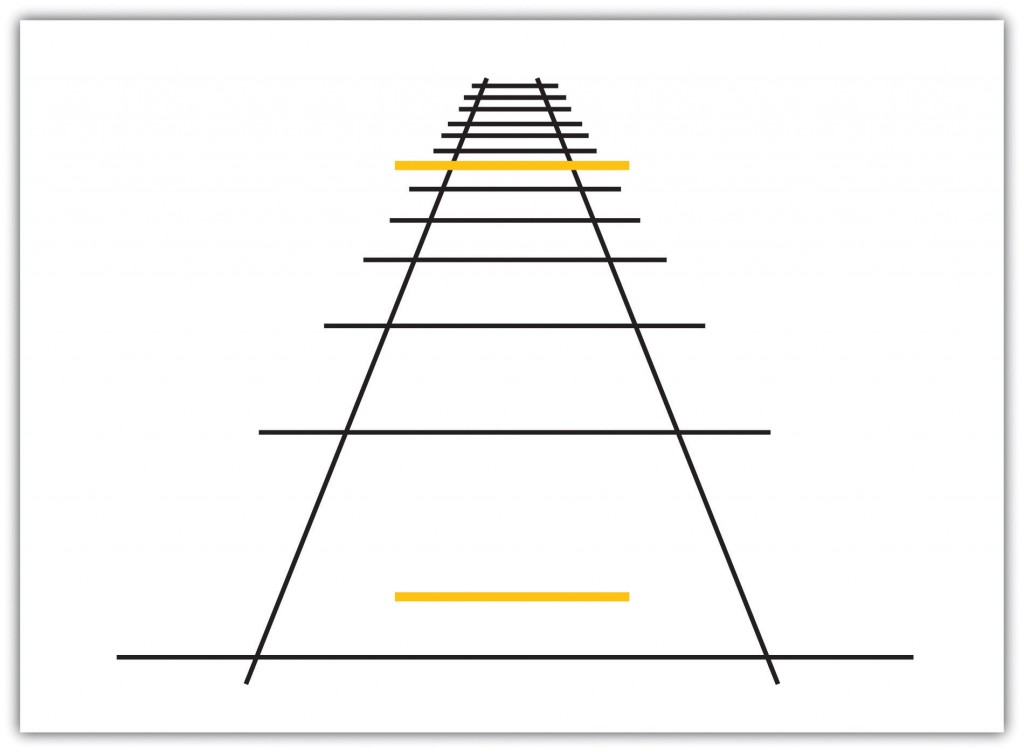

The Ponzo illusion operates on the same principle. As you can see in Figure 2.7, the top yellow bar seems longer than the bottom one, but if you measure them you’ll see that they are exactly the same length. The monocular depth cue of linear perspective leads us to believe that, given two similar objects, the distant one can only cast the same size retinal image as the closer object if it is larger. The topmost bar therefore appears longer.

Figure 2.7: The Ponzo Illusion. The Ponzo illusion is caused by a failure of the monocular depth cue of linear perspective. Both bars are the same size, even though the top one looks larger.

Illusions demonstrate that our perception of the world around us may be influenced by our prior knowledge. But the fact that some illusions exist in some cases does not mean that the perceptual system is generally inaccurate — in fact, humans normally become so closely in touch with their environment that the physical body and the particular environment that we sense and perceive becomes embodied — that is, built into and linked with our cognition, such that the world around us becomes part of our brain (Calvo & Gomila, 2008). The close relationship between people and their environments means that, although illusions can be created in the lab and under some unique situations, they may be less common with active observers in the real world (Runeson, 1988).

The Important Role of Expectations in Perception

Our emotions, mindset, expectations, and the contexts in which our sensations occur all have a profound influence on perception. People who are warned that they are about to taste something bad rate what they do taste more negatively than people who are told that the taste won’t be so bad (Nitschke et al., 2006), and people perceive a child and adult pair as looking more alike when they are told that they are parent and child (Bressan & Dal Martello, 2002). Similarly, participants who see images of the same baby rate it as stronger and bigger when they are told it is a boy as opposed to when they are told it is a girl (Stern & Karraker, 1989), and research participants who learn that a child is from a lower-class background perceive the child’s scores on an intelligence test as lower than people who see the same test taken by a child they are told is from an upper-class background (Darley & Gross, 1983a). Plassmann et al. (2008) found that wines were rated more positively and caused greater brain activity in brain areas associated with pleasure when they were said to cost more than when they were said to cost less. And even experts can be fooled: professional referees tended to assign more penalty cards to soccer teams for videotaped fouls when they were told that the team had a history of aggressive behavior than when they had no such expectation (Jones et al., 2002).

Psychology in Everyday Life: How Understanding Sensation and Perception Can Save Lives

Human factors is the field of psychology that uses psychological knowledge, including the principles of sensation and perception, to improve the development of technology. Human factors has worked on a variety of projects, ranging from nuclear reactor control centers and airplane cockpits to cell phones and websites (Proctor & Van Zandt, 2008). For instance, human factors has made substantial contributions to airline safety. About two-thirds of accidents on commercial airplane flights are caused by human error (Nickerson, 1998a). Psychologist Kraft (1978) hypothesized that as planes land, with no other distance cues visible, pilots may be subjected to a type of moon illusion, in which the city lights beyond the runway appear much larger on the retina than they really are, deceiving the pilot into landing too early. Kraft’s findings caused airlines to institute new flight safety measures, where copilots must call out the altitude progressively during the descent, which has probably decreased the number of landing accidents.

Figure 2.8 presents images of an airplane instrument panel before and after it was redesigned by human factors psychologists. The redesigned digital cockpit shows a marked improvement in usability with color-coded and multifunctional controls, LCD and 3-D graphics, and changeable text sizes that increase readability.

One important aspect of the redesign was based on the principles of sensory adaptation. Displays that are easy to see in darker conditions quickly become unreadable when the sun shines directly on them, and it takes the pilot a relatively long time to adapt to the suddenly much brighter display. Human factors psychologists used these principles to develop an automatic control mechanism that senses the ambient light and automatically adjusts the display intensity for optimal readability under a wide range of conditions (Silverstein et al., 1990; Silverstein & Merrifield, 1985).

Figure 2.8: Airplane instrument panel before (left) and after (right) it was redesigned by human factors psychologists.

Key Takeaways

- Sensation is the process of receiving information from the environment through our sensory organs. Perception is the process of interpreting and organizing the incoming information so that we can understand it and react accordingly.

- The retina has two types of photoreceptor cells: rods, which detect brightness and respond to black and white, and cones, which respond to red, green, and blue. Colour blindness occurs when people lack function in the red- or green-sensitive cones. Feature detector neurons in the visual cortex help us recognize objects, and some neurons respond selectively to faces and other body parts.

- The ability to perceive depth occurs as the result of binocular and monocular depth cues.

- Perceptual constancy allows us to perceive an object as the same, despite changes in sensation.

- Cognitive illusions are examples of how our expectations can influence our perceptions.

Exercises

- Practice: List some ways that the processes of visual perception help you engage in an everyday activity, such as driving a car or riding a bicycle.

- Discussion: What are some cases where your expectations about what you thought you were going to experience influenced your perceptions of what you actually experienced?

2.3 Glossary

binocular depth cues

Depth cues that are created by retinal image disparity — that is, the space between our eyes — and which thus require the coordination of both eyes

computer vision

Machines or algorithms that are built to mimic the human sensation and perception system

convergence

the inward turning of our eyes that is required to focus on objects that are less than about 50 feet away from us

depth cues

Messages from our bodies and the external environment that supply us with information about space and distance

embodied

The particular environment that we sense and perceive becomes built into and linked with our cognition

human factors

The field of psychology that uses psychological knowledge, including the principles of sensation and perception, to improve the development of technology

iris

The coloured part of the eye that controls the size of the pupil by constricting or dilating in response to light intensity

McGurk Effect

An error in perception that occurs when we misperceive sounds because the audio and visual parts of the speech are mismatched

Mueller-Lyer Illusion

An illusion in which one line segment looks longer than another based on converging or diverging angles at the ends of the lines.

optic nerve

A collection of millions of ganglion neurons that sends vast amounts of visual information to the brain

perception

The process of interpreting and organizing the incoming information so that we can understand it and react accordingly