Chapter 4 Short-term and Working Memory

Working memory is like your mind’s workspace: a limited capacity system for storage and processing of information. Have you ever noticed that it’s hard to understand someone if they throw too much information at you at once? That experience of confusion when receiving more information than we can process is called working memory overload. But working memory does more than simply hold information, it also processes and manipulates whatever information you’re currently thinking about. In fact, the name scientists use for the system changed over time from “short-term memory” to “working memory” to emphasize the processing function of this stage of memory.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Distinguish between the concepts of short-term memory and working memory.

- Explain the roles of knowledge and distinctiveness in working memory capacity.

- Explain the evidence for the separate components of working memory.

When people talk about memory, they are describing the mind’s ability to encode, store, and retrieve information. Our ability to remember is what allows us to learn from our experiences. How does our brain store and later retrieve information? Many different models of memory have evolved in an attempt to answer this question. Distinctions are drawn between working memory and long-term memory based on the period of time information is accessible after it is first encountered. Sensory memory has the smallest time span for accessibility of information. With short-term and working memory, information is accessible seconds to minutes after it is first encountered. Long-term memory has an accessibility period from minutes to years to decades.

In more recent research, the distinctions between working and long-term memory focus more so on whether attention is being used to actively hold things in mind. Under that interpretation, working memory lasts as long as attention is involved. While the focus of this chapter is on working memory, we will start describing what working memory used to be called: short-term memory.

4.1 Short-Term Memory

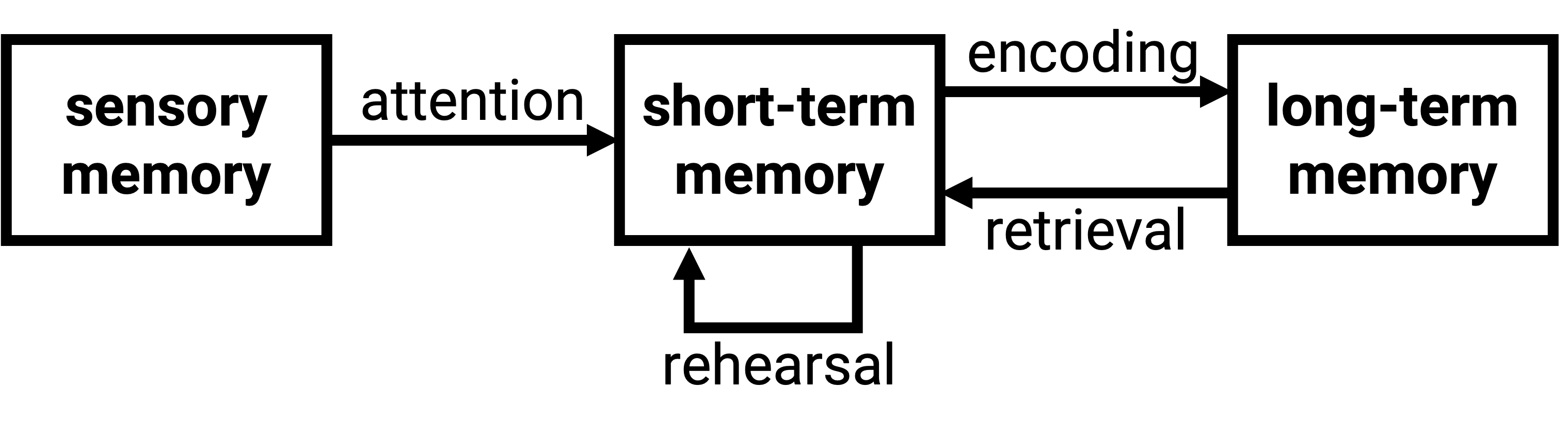

Figure 4.1: Atkinson and Shiffrin’s Modal Model of Memory.

In the middle of the 20th century, many scientists were interested in short-term memory (STM), or how humans can hold small amounts of information actively in their minds for a short period of time. Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968) wrote a landmark paper that synthesized existing evidence on how memory functions and proposed a model of memory referred to as the Modal Model of Memory (4.1). In this model, information first enters sensory memory, which is a highly transient storage space for information that recently entered your sensory system. This information is high quality but fades away very quickly. Have you ever had the experience of hearing someone say something when you weren’t really paying attention, then repeating it immediately in your head, and then being able to understand it? For about three seconds, you can play back the auditory information that you just heard. You can even hear it in the speaker’s original tone of voice! You use your sensory memory to do this.

The next stage the Modal Model is short-term memory. Information that you pay attention to from sensory memory enters the short-term memory store. As the name suggests, information is retained in the Short Term Memory for a rather short period of time (15–30 seconds). In order to keep information in short-term memory, the model suggests you must rehearse it.

How much information can be held in short-term memory? According to George Miller (1959), the capacity of short-term memory is five to nine pieces of information (The magical number seven, plus or minus two). That’s why I could read a 7-digit phone number to you and have you repeat it back, but if I read you my 16-digit credit card number and asked you to repeat it to me, it would probably feel impossible. What counts as a “piece of information?” A piece of information is called a chunk, which is a meaningful unit of information. All of the following can be chunks: single digits or letters, whole words, or even sentences. An example of chunking information is the following.

Try to remember the following digits:

1 2 2 5 1 9 8 4

Now try to remember the same digits, but group them differently:

12 - 25 - 1984

With this strategy you chunked eight pieces of information (eight digits) to three pieces to remember them as a date on the calendar. You could chunk the information even more efficiently if you recognize 12-25 as a single unit, the date of Christmas. The process of chunking is the process of combining smaller units of information into larger, meaningful units of information. The term “meaningful” is subjective— a meaningful chunk for you might not be a meaningful chunk for me. For example, 3 5 3 1 might not make a meaningful chunk for everyone, but if you’re a student of football history, you might chunk it as 35–31: the final score of the Super Bowl XIII, when Jackie Smith dropped a touchdown pass in the end zone.

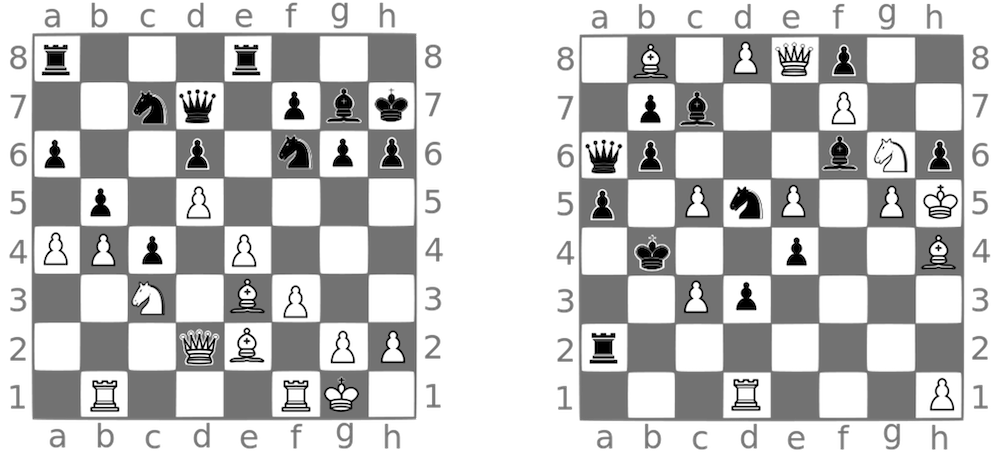

A famous experiment concerned with chunking was conducted by Chase & Simon (1973) with novices and experts in chess playing. When asked to remember certain arrangements of chess pieces on a board, the experts performed significantly better that the novices. However, if the pieces were arranged randomly, i.e. not corresponding to possible game situations, both the experts and the novices performed equally poorly. The reason is that expert chess players spend hours studying chess games and memorizing board configurations. When trying to remember the layout of a chess board, the experienced chess players do not try to remember single positions of the figures in the correct game situation, but whole chunks of figures from their memory. In random board configurations this strategy cannot work, which shows that chunking (as done by experienced chess players) enhances the performance only in specific memory tasks.

Figure 4.2: Left: A chessboard in the middle of a real game. Right: A random arrangement of chess pieces. Chess experts have significantly better memory for real boards, but perform more like novices for random board configurations.

The third stage of the Modal Model is long-term memory. According to the Modal Model, the important processes for long-term memory are storage (i.e., transferring information from short-term to long-term memory), search (i.e., locating information in the long-term store) and retrieval (i.e., recovering the information from the long-term store). Long-term memory will be the focus of chapters 5 and 6.

From the Modal Model to Baddeley’s Working Memory Model

Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968) formulated the Modal Model as a foundational framework to guide researchers in developing memory models (Wixted, 2024). Beyond the simple model, they depicted the short-term store as the central hub of memory activity (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1971). Building on these ideas, Baddeley & Hitch (1974) proposed their Working Memory Model. While the Modal Model was relatively focused on the memory function of the short-term store, Baddeley and Hitch described a working memory as chiefly an information processing system. Notice the difference in terminology: Atkinson and Shiffrin called the temporary memory space “short-term memory” while Baddeley and Hitch use the term “working memory.” Atkinson and Shiffrin would not dispute this terminology – indeed, the first page of their introduction says “the short-term store is the subject’s working memory” (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968, p. 90) – though it has become a common misconception that their 1968 paper asserts that short-term memory is limited to simple storage (Wixted, 2024). Today, scientists may still use the term “short-term memory” when discussing the temporary storage of simple items, but “working memory” has become the preferred term, emphasizing the role of the system in complex cognition.

4.2 Working Memory

According to Baddeley, working memory is capable of both storage and manipulation of incoming information. Baddeley and Hitch’s 1974 model consists of three parts: two storages spaces called the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketch pad, and a control unit call the central executive.

We will consider each part in turn: The Phonological Loop is responsible for auditory and verbal information, such as phone numbers, people’s names, or general conversation. One source of evidence that we have a special storage space for auditory information is the phonological similarity effect. Read the following list of words, then look away and try to repeat it to yourself:

car rig seam bar rose pop gear

And now try this one:

leak feed beak deep heat peek beat

If you are like the participants in a study by Conrad (1964), your performance was worse on the second list than it was in the first. The reason the second list was harder is because when you read the words on the page, you translate them into an acoustic form. Because the words in the second list sound alike, you are more likely to confuse them as you repeat them in your phonological loop.

How much information can the phonological loop hold? Researchers have found that the magical number seven plus or minus two does not explain all of the available data. While Miller’s magical number is approximately accurate when English-speaking participants remember digits or letters, it doesn’t hold when the length of the words is manipulated.

To demonstrate this to yourself, try to remember the following list of words:

lip base rain duck bib fall gate

And now try this one:

carpenter radiate thermostat honesty photograph dinosaur horizon

Both lists are seven words long, and yet people are much worse at a list like the second one (Baddeley et al., 1975). This is called the word-length effect: lists of short words are recalled better than lists of long words. If you think back to early research on short-term memory, this result is surprising! According to Miller’s magical number, these lists should be remembered equally well because they contain the same number of items. Findings like the word length effect led researchers to conclude that the capacity of the phonological loop should not be measured in number of items, but in amount of time instead: the phonological loop can hold about two seconds of auditory information, which it can replay over and again through an active articulatory process. Imagine you have two seconds of tape— you could fit a lot more short words on it than long words!

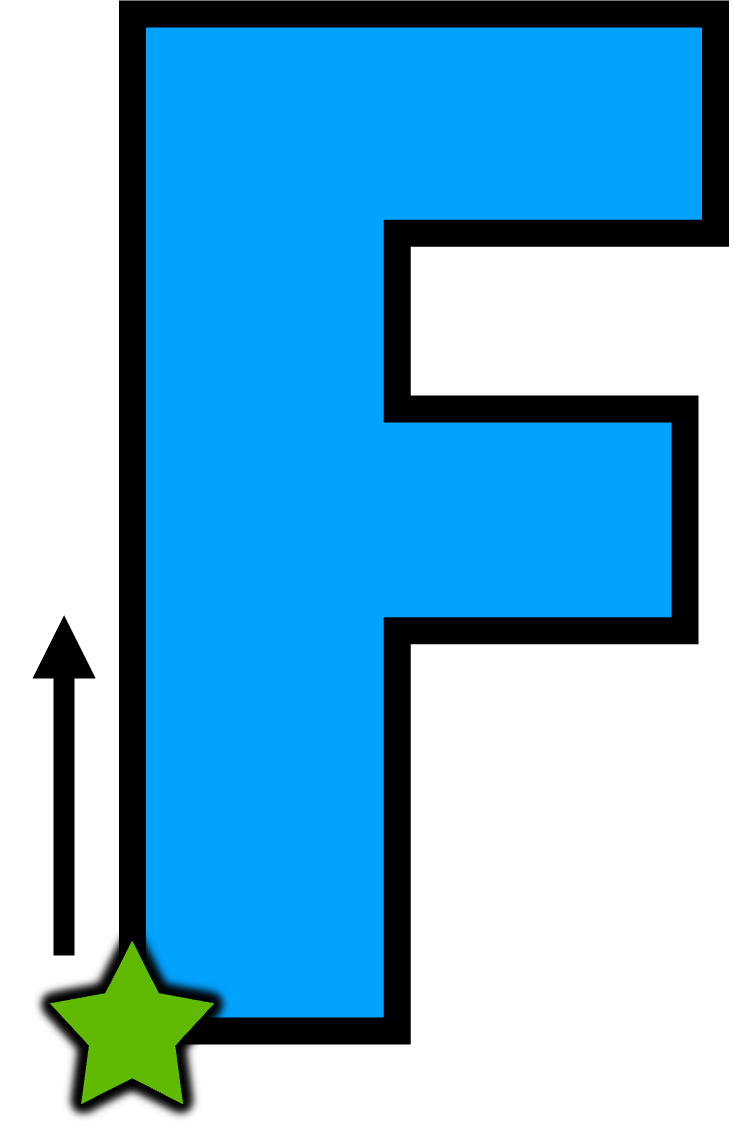

The next component of working memory is the visuospatial sketch pad, which handles visual and spatial information. Like the phonological loop, the visuospatial sketch pad is primarily a storage space. What evidence do we have that visual and spatial information is stored independently from auditory and verbal information? Look at the block letter F to the right. In an example experiment, you would be instructed to memorize the letter, and then, starting with the starred corner and then traveling up and around the letter, indicate whether each corner is an outside corner (like the starred corner) or an inside corner (like the fifth corner as you travel around the shape). In one condition, participants would verbally say “outside” or “inside” for each corner. In the other condition, participants would point at the words “outside” and “inside” displayed in front of them for each corner. Brooks (1968) conducted an experiment similar to this one, and found that participants were much better at the task when they could verbally indicate the type of corner than when they had to point. Why? We have two storage spaces in working memory and each of them is limited in capacity. Mentally traveling around the block letter and judging the corners is a spatial task, and so it puts a load on the visuospatial sketch pad. If you add pointing on top of that, participants’ visuospatial sketch pads get overloaded and they struggle to do both simultaneously. If instead you allow participants to respond verbally, they are distributing the response aspect of the task onto the phonological loop. That way, neither storage system becomes overloaded.

We have seen that the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketch pad deal with different kinds of information, which nonetheless have to interact in order to do certain tasks. The component that connects these two systems is the central executive. The central executive coordinates the activity of both the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketch pad. In fact, most of the “working” part of working memory is done by the central executive.

The functions of the central executive can be broken down into three categories: shifting, updating, and inhibition (Miyake et al., 2000). Shifting refers to engaging and disengaging from tasks, such as switching your attention back and forth between watching television and doing the dishes. Updating refers to monitoring information that is incoming into working memory, and making room for it by replacing old information in working memory. Inhibition refers to the deliberate inhibition of responses, such as when the ticket taker says “enjoy your movie!” and you stop yourself from saying, “you too!”

The episodic buffer

Science is an ongoing process, and so despite the usefulness of Baddeley and Hitch’s working memory model, it was updated in 2000 to add another component: the episodic buffer (Baddeley, 2000). The episodic buffer is a limited capacity, temporary storage system that is controlled by the central executive and integrates information from a variety of sources including long-term memory. The episodic buffer was added to help account for human performance in complex cognition— for example, we can remember many more words when we remember a meaningful sentence than when we remember a random word list. The episodic buffer was added to help account for this and other phenomena in which working memory performance seemingly requires additional storage as well as interfacing with long-term memory. The addition of the Episodic Buffer paralleled broader movement in the field towards thinking about how knowledge impacts working memory capacity.

Working Memory, Meaning, and Distinctiveness

People not only have better memory for items that are more meaningful to them (e.g., you can remember 7 real-world objects better than 7 colors), but also for items that are distinct (Brady et al., 2016). The idea that we have better memory for more distinct items in a set (i.e., remembering blue vs. red is easier than remembering blue vs. teal) has been around for almost a century. Von Restorff (1933) showed that certain things were more or less memorable, not in and of themselves, but in relation to how distinct they were from other stimuli in the set. This idea has recently re-emerged in more recent research on working memory as a way to explain capacity limitations as well as memory errors.

The finding that distinctive items can be remembered better than similar items has been reproduced many times, with many different kinds of stimuli. For instance, expert radiologists have the best memory for mammograms that are the most distinct from other mammograms (Schill et al., 2021).

Research into memory and distinctiveness has also led to recent advances in understanding memory errors. For example, researchers have found that the similarity between two items can almost perfectly predict the memory errors we make. The more similar two items are, the more likely we are to think that the similar item was the thing we were trying to remember. (Schurgin et al., 2020). This has many real world implications such as in the field of eyewitness testimony, which will be touched on in later chapters.

Key Takeaways

- We are very limited in how much information we can hold actively in our minds. Early research showed we could hold 7 plus or minus two chunks of information. More recent research focuses more on characterizing working memory dynamics.

- Working memory has three helper systems: the phonological loop, the visuospatial sketchpad, and the episodic buffer. The central executive controls attention and coordinates these helper systems.

- Our prior knowledge has a large influence on how much information we can hold in working memory; for example we can hold more information if we can group it into meaningful chunks. Distinctiveness also plays an important role.

Exercises

- Discuss. While regular people can hold around 7 digits in working memory at once, competitive memorizers can hold over a thousand. Incredibly, these people don’t have enhanced working memory capacity – they just spend a lot of time practicing memory strategies! Based on what you’ve learned about chunking, what memory strategies might these competitors use?

- Practice. Make lists of short and long words, and quiz your friends to see which they can remember more of.

4.3 Glossary

central executive

A component of working memory that controls attention and coordinates the activity of the helper systems

sensory memory

Highly transient storage space for information that recently entered your sensory system

short-term memory

Small amounts of information actively held in the minds for a short period of time