Chapter 5 Long-term Memory

Our memories allow us to do relatively simple things, such as remembering where we parked our car or the name of the current governor of California, but also allow us to form complex memories, such as how to ride a bicycle or to write a computer program. Moreover, our memories define us as individuals — they are our experiences, our relationships, our successes, and our failures. Without your memories, would you still be you?

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Compare and contrast working memory and long-term memory, identifying the features that define each.

- Compare and contrast explicit and implicit memory, identifying the features that define each.

- Label and review the principles of encoding, storage, and retrieval.

- Describe how the context in which we learn information can influence our memory of that information.

5.1 Working Memory Vs. Long-Term Memory

As we discussed in the last chapter, working memory is a temporary storage space for information that is being actively stored and manipulated in consciousness. Information that is not rehearsed will be forgotten within 18 to 30 seconds. Long-term memory, on the other hand, is where we store everything from a few moments to the earliest thing we can remember. There is theoretically no upper limit to the amount of information we can store in long-term memory.

The Serial Position Curve

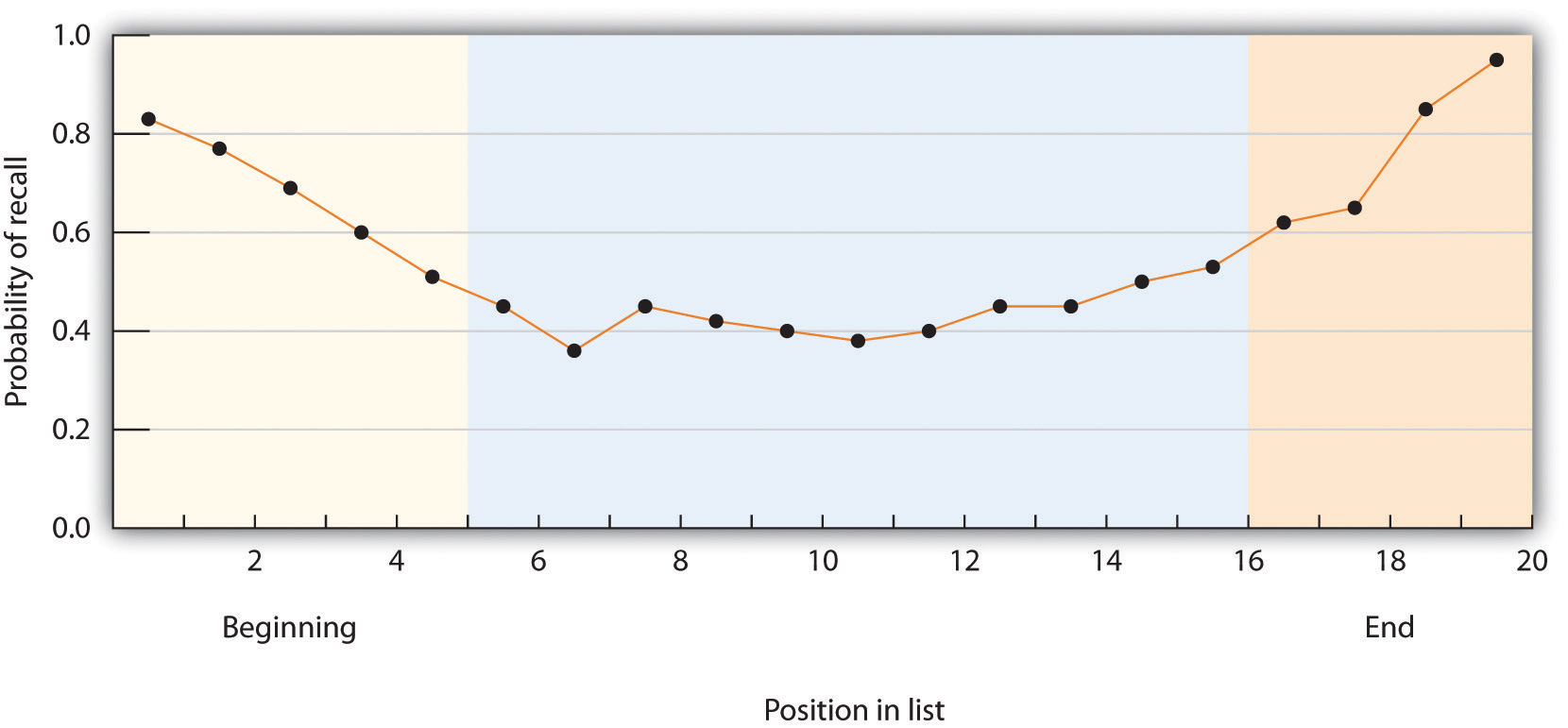

Figure 5.1: The serial position curve is the result of both primacy effects and recency effects.

The distinction between working memory and long-term memory can be demonstrated with the serial position curve. When we give people a long list of words one at a time (e.g., on flashcards) and then ask them to recall them, the results look something like those in 5.1. People are able to retrieve more words that were presented to them at the beginning and the end of the list than they are words that were presented in the middle of the list. This pattern, known as the serial position curve, is caused by two retrieval phenomenon: The primacy effect refers to a tendency to better remember stimuli that are presented early in a list. The recency effect refers to the tendency to better remember stimuli that are presented at the end of a list.

Primacy and recency effects can be explanied in terms of the effects of rehearsal on short-term and long-term memory (A. D. Baddeley, 1990). Because we can keep the last words that we learned in the presented list in short-term memory by rehearsing them before the memory test begins, they are relatively easily remembered. So the recency effect can be explained in terms of maintenance rehearsal in short-term memory— the most recent words are still available in short-term memory at the time of recall. And the primacy effect can also be explained by rehearsal—when we hear the first word in the list we start to rehearse it, making it more likely that it will be moved from short-term to long-term memory. And the same is true for the other words that come early in the list. But for the words in the middle of the list, this rehearsal becomes much harder, making them less likely to be moved to long-term memory

Brains Vs. Computers

The distinction between short-term memory and long-term memory might remind you of the distinction between RAM and ROM in a computer. Are brains just computers that live in our heads? Not exactly. Here are some key differences:

- In computers, information can be accessed only if one knows the exact location of the memory. In the brain, information can be accessed through spreading activation from closely related concepts. Further, there is no exact location of a stored memory in the brain.

- Computers differentiate memory (e.g. the hard drive) from processing (the central processing unit), but in brains there is no such distinction.

- In the brain (but not in computers) existing memory is used to interpret and store incoming information, and retrieving information from memory changes the memory itself.

- The brain is self-organizing and self-reparing, but computers are not. If a person suffers a stroke, neural plasticity will help them recover.

- The brain is significantly more complex than any current computer. The brain is estimated to have 25,000,000,000,000,000 (25 million billion) interactions among axons, dendrites, neurons, and neurotransmitters, and that doesn’t include the approximately 1 trillion glial cells that may also be important for information processing and memory.

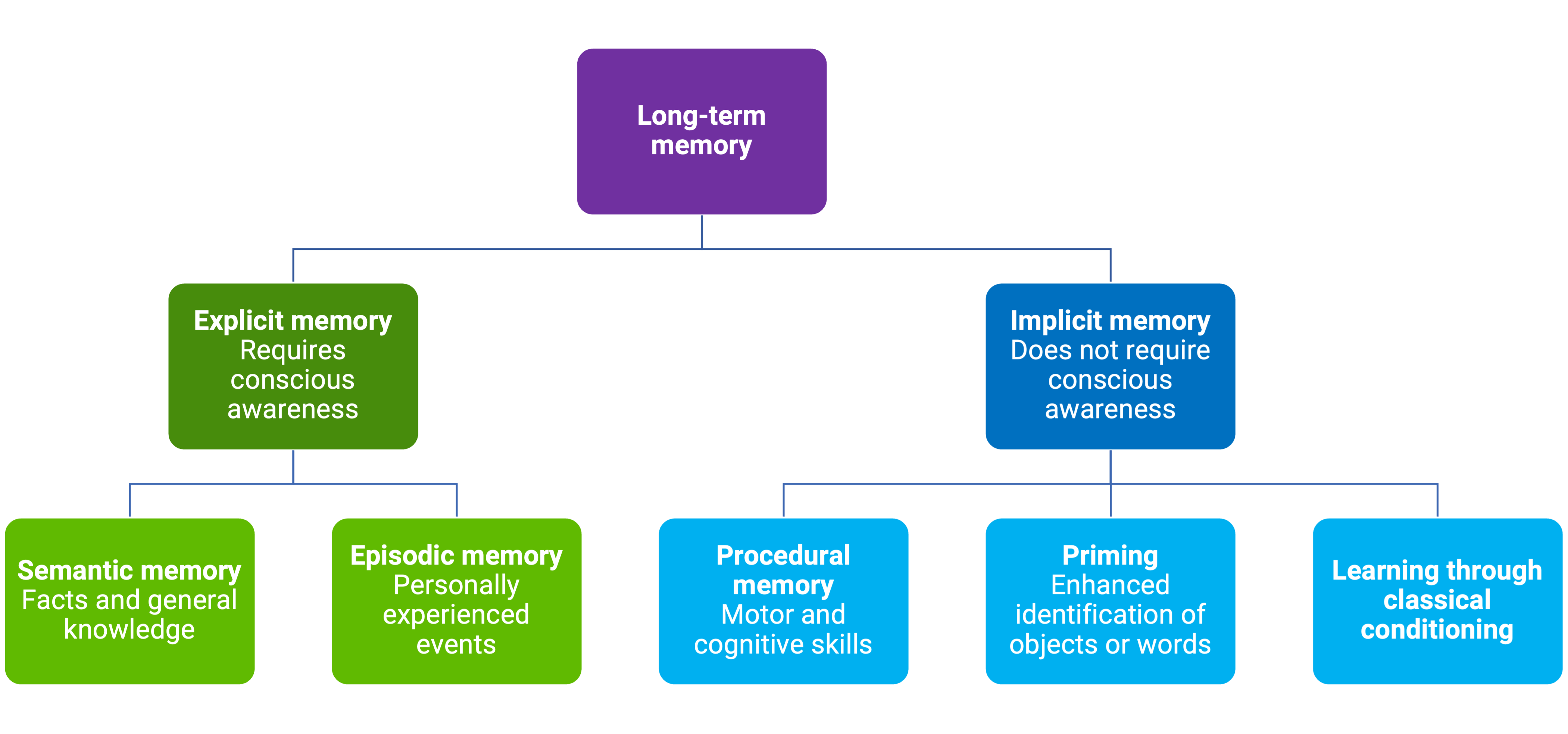

5.2 Structure

According to Baddeley’s model, working memory includes a central executive, phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, and episodic buffer. What is the structure of long-term memory? As you can see in Figure 5.2, long-term memory can be divided into two major categories of memory types: explicit memory and implicit memory, which can be further divided into multiple sub-types: semantic, episodic, procedural, priming, and conditioning memory.

Figure 5.2: Structure of long-term memory.

Explicit Memory

The first form of long-term memory we will discuss is explicit memory. We are measuring explicit memory when we assess memory by asking a person to consciously remember things. Explicit memory refers to knowledge or experiences that can be consciously remembered. There are two types of explicit memory: episodic and semantic. Episodic memory refers to the firsthand experiences that we have had (e.g., recollections of our high school graduation day or of the fantastic dinner we had in New York last year). [Semantic memory] refers to our knowledge of facts and concepts about the world (e.g., that the absolute value of −90 is greater than the absolute value of 9 and that one definition of the word “affect” is “the experience of feeling or emotion”).

Explicit memory is assessed using measures in which the individual being tested must consciously attempt to remember the information. A recall memory test is a measure of explicit memory that involves bringing from memory information that has previously been remembered. We rely on our recall memory when we take an essay test, because the test requires us to generate previously remembered information. A multiple-choice test is an example of a recognition memory test, a measure of explicit memory that involves determining whether information has been seen or learned before.

Your own experiences taking tests will probably lead you to agree with the scientific research finding that recall is more difficult than recognition. Recall, such as required on essay tests, involves two steps: first generating an answer and then determining whether it seems to be the correct one. Recognition, as on multiple-choice test, only involves determining which item from a list seems most correct (Haist et al., 1992). Although they involve different processes, recall and recognition memory measures tend to be correlated. Students who do better on a multiple-choice exam will also, by and large, do better on an essay exam (Bridgeman & Morgan, 1996).

A third way of measuring memory is known as relearning (Nelson, 1985). Measures of relearning (or savings) assess how much more quickly information is processed or learned when it is studied again after it has already been learned but then forgotten. If you have taken some French courses in the past, for instance, you might have forgotten most of the vocabulary you learned. But if you were to work on your French again, you’d learn the vocabulary much faster the second time around. Relearning can be a more sensitive measure of memory than either recall or recognition because it allows assessing memory in terms of “how much” or “how fast” rather than simply “correct” versus “incorrect” responses. Relearning also allows us to measure memory for procedures like driving a car or playing a piano piece, as well as memory for facts and figures.

Implicit Memory

While explicit memory consists of the things that we can consciously report that we know, implicit memory refers to knowledge that we cannot consciously access. However, implicit memory is nevertheless exceedingly important to us because it has a direct effect on our behavior. Implicit memory refers to the influence of experience on behavior, even if the individual is not aware of those influences. As you can see in Figure 5.2, there are three general types of implicit memory: procedural memory, classical conditioning effects, and priming.

Procedural memory refers to our often unexplainable knowledge of how to do things. When we walk from one place to another, speak to another person in English, dial a cell phone, or play a video game, we are using procedural memory. Procedural memory allows us to perform complex tasks, even though we may not be able to explain to others how we do them. There is no way to tell someone how to ride a bicycle; a person has to learn by doing it. The idea of implicit memory helps explain how infants are able to learn. The ability to crawl, walk, and talk are procedures, and these skills are easily and efficiently developed while we are children despite the fact that as adults we have no conscious memory of having learned them. Also note that within procedural memory, it is often divided into three sub-types: cognitive, motor, and perceptual.

A second type of implicit memory is classical conditioning effects, in which we learn, often without effort or awareness, to associate neutral stimuli (such as a sound or a light) with another stimulus (such as food), which creates a naturally occurring response, such as enjoyment or salivation. The memory for the association is demonstrated when the conditioned stimulus (the sound) begins to create the same response as the unconditioned stimulus (the food) did before the learning.

The final type of implicit memory is known as priming, or changes in behavior as a result of experiences that have happened frequently or recently. Priming refers both to the activation of knowledge (e.g., we can prime the concept of kindness by presenting people with words related to kindness) and to the influence of that activation on behavior (people who are primed with the concept of kindness may act more kindly).

One measure of the influence of priming on implicit memory is the word fragment test, in which a person is asked to fill in missing letters to make words. You can try this yourself: First, try to complete the following word fragments, but work on each one for only three or four seconds. Do any words pop into mind quickly?

- _ i b _ a _ y

- _ h _ s _ _ i _ n

- _ o _ k

- _ h _ i s _

Now read the following sentence carefully:

“He got his materials from the shelves, checked them out, and then left the building.”

Then try again to make words out of the word fragments.

I think you might find that it is easier to complete fragments 1 and 3 as “library” and “book,” respectively, after you read the sentence than it was before you read it. However, reading the sentence didn’t really help you to complete fragments 2 and 4 as “physician” and “chaise.” This difference in implicit memory probably occurred because as you read the sentence, the concept of “library” (and perhaps “book”) was primed, even though they were never mentioned explicitly. Once a concept is primed it influences our behaviors, for instance, on word fragment tests.

Our everyday behaviors are influenced by priming in a wide variety of situations. Seeing an advertisement for cigarettes may make us start smoking, seeing the flag of our home country may arouse our patriotism, and seeing a student from a rival school may arouse our competitive spirit. And these influences on our behaviors may occur without our being aware of them.

5.3 Encoding, Retrieval, and Consolidation

Imagine you are able to perfectly study for an exam. You take notes in lecture and read the textbook as the quarter moves along. As you approach the exam, you develop study materials, test yourself on the information, and go to the professor’s office hours to ask about the parts you find the most difficult. The day before the exam, you explain all of the important concepts from class to your best friend. You get a good night’s sleep, and the next morning you find that remembering the important concepts from class feels relatively easy. The questions on the exam include bits of information that help you retrieve the concepts that you studied so hard to understand. You leave feeling like your exam performance was a good reflection of the hard work you put in to studying.

Figure 5.3: Photo by Robert Bye on Uplash.

In this situation, you were able to successfully encode, retrieve, and consolidate the information you sought to learn. Encoding refers to storing new information in long-term memory. This is the process you engaged in during lecture and studying. Retrieval refers to remembering information from long-term memory. This is what you did when you tested yourself on information and when you took the exam. Consolidation is the stabilization of long-term memories after initial encoding. Consolidation insulates your memories from interference from new memories that are formed. Interference causes a retreival failure of the target memory. Consolidation is aided by sleep, which is why you felt even more confident in your knowledge by getting a good night of sleep before the exam. The following sections will discuss the factors that affect encoding, retrieval, and consolidation.

Encoding

Maintenance rehearsal

Maintenance rehearsal is a type of memory rehearsal that is useful in maintaining information in working memory. Because this usually involves repeating information without thinking about its meaning or connecting it to other information, the information is not usually transferred to long term memory. That is, maintenance rehearsal does not usually lead to encoding new long-term memories. An example of maintenance rehearsal would be repeating a phone number mentally, or aloud until the number is entered into the phone to make the call. The number is held in working memory long enough to make the call, but never transferred to long term memory. An hour, or even five minutes after the call, the phone number will no longer be remembered.

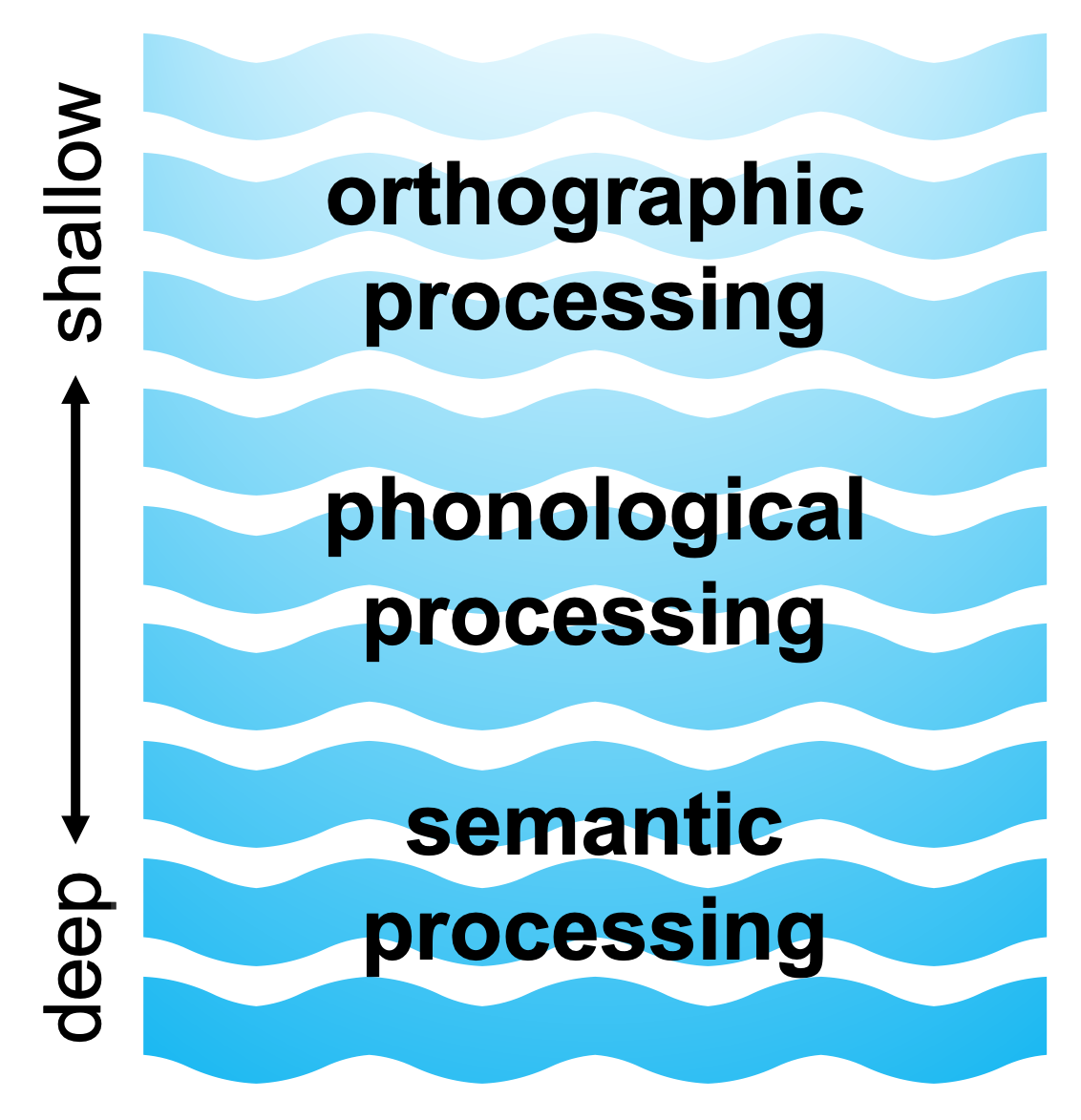

Depth of processing

The levels-of-processing effect, identified by Fergus Craik & Tulving (1975), describes memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing at encoding. Deeper levels of analysis produce more elaborate, longer-lasting, and stronger memory traces than shallow levels of analysis. Depth of processing falls on a shallow to deep continuum. Shallow processing (e.g., processing based on phonemic and orthographic components) leads to a fragile memory trace that is susceptible to rapid decay. Conversely, deep processing (e.g., semantic processing) results in a more durable memory trace.

This theory contradicts the multi-store Atkinson-Shiffrin memory model which represents memory strength as being continuously variable, the assumption being that rehearsal always improves long-term memory. They argued that rehearsal that consists simply of repeating previous analyses (maintenance rehearsal) doesn’t enhance long-term memory.

Figure 5.4: Levels of processing based on evidence from Craik and Tulving.

In a study from Craik & Tulving (1975) participants were given a list of 60 words. Each word was presented along with three questions. The participant had to answer one of them. Those three questions were in one of three categories. One category of questions was about how the word was presented visually (“Is the word shown in italics?”). This category of questions was meant to promote orthographic processing, or processing related to how the word was written. The second category of questions was about the phonemic qualities of the word (“Does the word begin with the sound ‘bee’?”). This category was meant to promote phonological processing, or processing related to how the words sound. The third category of questions was presented so that the reader was forced to think about the word within a certain context (“Can you meet one in the street [a friend]”?). This category of questions was meant to promote semantic processing, or processing related to the words’ meaning. The result of this study showed that the more deeply words were processed at encoding, the more likely they were to be remembered later.

Later work by Rogers et al. (1977) expanded the levels-of-processing effect by demonstrating an even deeper level of processing than semantic processing: self-referential processing (e.g., “Does this word describe you?”). This is referred to as the self-reference effect: processing words in terms of their relation to yourself promotes an even higher rate of recall than normal semantic processing.

The Testing Effect

The testing effect is that retrieval from memory rather than simple restudy is a more effective way to cement information into memory. For example, if you are trying to learn that the mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell, you could either reread this fact or create a flashcard asking “what is the powerhouse of the cell?” and retrieving from memory that it is the “mitochondria”. The latter way is a more effective study strategy. Particularly in the case when correct answer feedback is provided. The testing effect has been ubiquitously found in a variety of declarative learning context, so regardless of what you are trying to learn, it is an effective method (Kromann et al., 2009; Lantz, 2010; Larsen et al., 2009; McDaniel et al., 2007; Nungester & Duchastel, 1982; Pan et al., 2015; Rickard & Pan, 2018).

Although the testing effect was first noted by Abbot (1909), the past decade has seen a resurgence in research. With this resurgence is also a better understanding of potential mechanisms of the testing effect. Our current understanding has two leading categories of mechanisms. One theory assumes, active retrieval of a memory reinstates the previous contexts, which strengthens said memory and that memory search is restricted through episodic cues, making it quicker to find the memory Karpicke et al. (2014). A newer theory proposes that the testing effect is caused by the simple fact that testing causes two memories to be created, a study memory initially created during the initial acquisition of information and a test memory that is created during testing. Further, testing with correct answer feedback will always strengthen the study memory. Thus, the testing effect is the result of the fact that there are two potential memories that could be retrieved for the same bit of information Gupta et al. (2022).

The Spacing Effect

The spacing effect, which isthe benefit of temporally spaced practice relative to massed practice, is one of the most robust phenomena that improves declarative memory (A. S. Benjamin & Tullis, 2010; Cepeda et al., 2008; Lohnas & Kahana, 2014; Mozer et al., 2009; Polyn et al., 2009). Or in other words, spacing out your learning versus cramming for an exam the night before will yield better retention over a longer period of time. Note that this is the spaced repetition of the same information and not different information.

In general, models propose three potential mechanisms of the spacing effect. contextual drift, study-phase retrieval, and multiple learning time scales. Contextual drift refers to the diversity of contexts at each study time point. The more diverse the contexts over encounters, the stronger the resulting memory. Study-phase retrieval is the reactivation of a prior memory, including its original context, upon restudy. Thus, upon each encounter of an item, the prior memory of that item will be reactivated, increasing its strength. Information can be represented at different time scales. Some information can only be represented at fast time scales and other information can only be represented at slower time scales. For example, observed contexts of information is most likely to be represented at slower time scales.

Used together, the testing effect and the spacing effect are two of the most robust and effective strategies for learning.

Retrieval

Information stored in the memory is retrieved by way of association with other memories. Some memories can not be recalled by simply thinking about them. Rather, one must think about something associated with it. For example, if someone tries and fails to recollect the memories he had about a vacation he went on, and someone mentions the fact that he hired a classic car during this vacation, this may make him remember all sorts of things from that trip, such as what he ate there, where he went and what books he read.

Figure 5.5: Photo albums can be effective sources of retrieval cues. Photo by BBH Singapore on Uplash.

Encoding Specificity Principle

The encoding specificity principle is the general principle that memory is best when the conditions at encoding match the conditions at retrieval. For example, take the song on the radio: perhaps you heard it while you were at a terrific party, having a great, philosophical conversation with a friend. Thus, the song became part of that whole complex experience. Years later, even though you haven’t thought about that party in ages, when you hear the song on the radio, the whole experience rushes back to you. In general, the encoding specificity principle states that, to the extent a retrieval cue (the song) matches or overlaps the memory trace of an experience (the party, the conversation), it will be effective in evoking the memory. One example of the encoding specificity principle is transfer-appropriate processing, in which memory is best when the type of cognitive processing at recall matches the type of cognitive processing at encoding. This was empirically shown in a study by Morris et al. (1977) using semantic and rhyme tasks. In a standard recognition test, memory was better following semantic processing compared to rhyme processing, as predicted by the levels-of-processing effect. However, in a rhyming recognition test, memory was better for those who engaged in rhyme processing compared to semantic processing. This adds a level of complexity to the levels-of-processing theory: while the levels-of-processing framework generally holds for a normal recognition test, performance on rhyming tests is actually better with phonological than semantic processing at encoding.

![Results from Morris and colleagues’ Transfer-Appropriate Processing experiment [@Morris1977, Experiment 1].](images/ch5/fig6.png)

Figure 5.6: Results from Morris and colleagues’ Transfer-Appropriate Processing experiment (Morris et al., 1977, Experiment 1).

Other facets of the encoding specificity principle include context-dependent memory. Context-dependent learning refers to an increase in retrieval when the external situation in which information is learned matches the situation in which it is remembered. Godden & Baddeley (1975) conducted a study to test this idea using scuba divers. They asked the divers to learn a list of words either when they were on land or when they were underwater. Then they tested the divers on their memory, either in the same or the opposite situation. The divers’ memory was better when they were tested in the same context in which they had learned the words than when they were tested in the other context. In this instance, the physical context itself provided cues for retrieval.

Whereas context-dependent memory refers to a match in the external situation between learning and remembering, state-dependent memory refers to superior retrieval of memories when the individual is in the same physiological or psychological state as during encoding. Research has found, for instance, that animals that learn a maze while under the influence of one drug tend to remember their learning better when they are tested under the influence of the same drug than when they are tested without the drug (Jackson et al., 1992). Research with humans finds that bilinguals remember better when tested in the same language in which they learned the material (Marian & Kaushanskaya, 2007). Mood states may also produce state-dependent learning. People who learn information when they are in a bad (rather than a good) mood find it easier to recall these memories when they are tested while they are in a bad mood, and vice versa. It is easier to recall unpleasant memories than pleasant ones when we’re sad, and easier to recall pleasant memories than unpleasant ones when we’re happy (Bower, 1981).

Consolidation

Memory consolidation is a category of processes that stabilize a memory after its initial acquisition.

Reduction of Interference

It is sometimes incorrectly stated that consolidation causes more learning. While this would be great if it were true (imagine learning more in our sleep!) this is a mischaracterization of what is actually occurring. It is more accurate to say that consolidation reduces the amount of interference from other memories when we go to retrieve a memory. Imagine a scenario where you study for class A at the beginning of the day and then go to class B and C that same day. All of the information from classes B and C have the potential to interfere with the retrieval of the information that you studied for class A. Consolidation reduces this problem. This can be illustrated from a study done by Gais et al. (2006). Participants in this study first studied English-German word pairs. Participants in one condition (the sleep condition) went to sleep within three hours of learning the pairs. Participants in the other condition (the awake condition) stayed awake for about 10 hours before sleeping. The next day, all groups were tested on their memory for those words. The researchers found that the sleep group forgot less material than the awake group. According to the researchers, this difference can be explained by a reduction in interference: the awake group learned a whole bunch of new information during the day, which had the potential to interfere with the previously learned information. The sleep group on the other hand, had little new information before sleep and also benefited from more immediate consolidation.

Sleep Consolidation

Deep sleep, or slow wave sleep (SWS), is associated with the consolidation of memories. Rasch et al. (2007) showed evidence for this by pairing items participants learned with a rose odor. During sleep, the researchers re-exposed participants to the same rose odor during different stages of sleep in order to reactivated the memories associated with the odor. They found that only re-exposure to the rose odor during deep sleep increased retention for declarative learning. This research approach is called targeted memory reactivation (see box). Importantly, the same result was not found for procedural memories. Researchers following this line of work have come to assume that dreams are a byproduct of the reactivation of brain areas during sleep. The dream experience itself is not what enhances memory performance but rather it is the reactivation of the neural circuits that causes this.

Targeted Memory Reactivation

Although sleep by itself does not cause more learning to occur, researchers can cause memories to be reactivated during sleep by exposing sleeping participants to odors or sounds associated with specific memories. This has been found in a variety of types of learning (Hu et al., 2020), though for some memory types, including some types of procedural learning, this reactivation does not seem to promote reduction in interference (Rasch et al., 2007). In general, targeted-memory-reactivation (TMR) has two steps. First participants learn information, which the researchers pair with another stimulus (for example, pairing a word pair with a certain smell). The participants then sleep while wearing sensors that detect their brain activity. When the researchers detect that the participant is in the desired stage of sleep, the paired stimulus is presented. This reactivates the memory that was originally learned while they were awake. This approach has largely been used to study possible mechanisms of consolidation. Some evidence currently supports the theory that memories are replayed while one sleeps. This promotes memory consolidation and leads to memory stabilization. With TMR, we can artificially induce this replay and examine possible effects that consolidation can have on memories. Further, researchers are also now beginning to examine sleep quality and its relation to TMR. Whitmore et al. (2022) used TMR to enhance face-name pairs. They replicated previous findings that TMR only works during deep sleep and that this effect is moderated by the amount of time spent in deep sleep

Key Takeaways

- Memory refers to the ability to store and retrieve information over time. For some things our memory is very good, but our active cognitive processing of information ensures that memory is never an exact replica of what we have experienced.

- Explicit memory refers to experiences that can be intentionally and consciously remembered, and it is measured using recall, recognition, and relearning. Explicit memory includes episodic and semantic memories. Implicit memory refers to the influence of experience on behaviour, even if the individual is not aware of those influences. The three types of implicit memory are procedural memory, classical conditioning, and priming.

- The capacity of long-term memory is large, and there is no known limit to what we can remember. Information is better remembered when it is meaningfully elaborated. Context- and state-dependent learning, as well as primacy and recency effects, influence long-term memory.

Exercises

- Plan a course of action to help you study for your next exam, incorporating as many of the techniques mentioned in this section as possible. Try to implement the plan.

- In the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the characters undergo a medical procedure designed to erase their memories of a painful romantic relationship. Would you engage in such a procedure if it were safely offered to you?

5.4 Glossary

classical conditioning effects

A type of implicit memory in which we learn, often without effort or awareness, to associate neutral stimuli with another stimulus, which creates a naturally occurring response

context-dependent learning

an increase in retrieval when the external situation in which information is learned matches the situation in which it is remembered

levels-of-processing effect

memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing at encoding

recall memory test

a measure of explicit memory that involves bringing from memory information that has previously been remembered

recognition memory test

a measure of explicit memory that involves determining whether information has been seen or learned before

relearning

a memory measurement that assesses how much more quickly information is processed or learned when it is studied again after it has already been learned but then forgotten

self-reference effect

processing words in terms of their relation to yourself promotes an even higher rate of recall than normal semantic processing

serial position curve

a graphic depiction of the likelihood of remembering items from a list based on the order in which they were presented